Julia Perry in Focus – the pioneering female composer still fighting to be heard

By RNCM Professor of Singing and Researcher, Michael Harper

Julia Perry was an exceptional and talented mid-twentieth century composer who achieved greatness in a world not moulded in her image. The latest in the RNCM’s In Focus series says there’s never been a more important time to take another look.

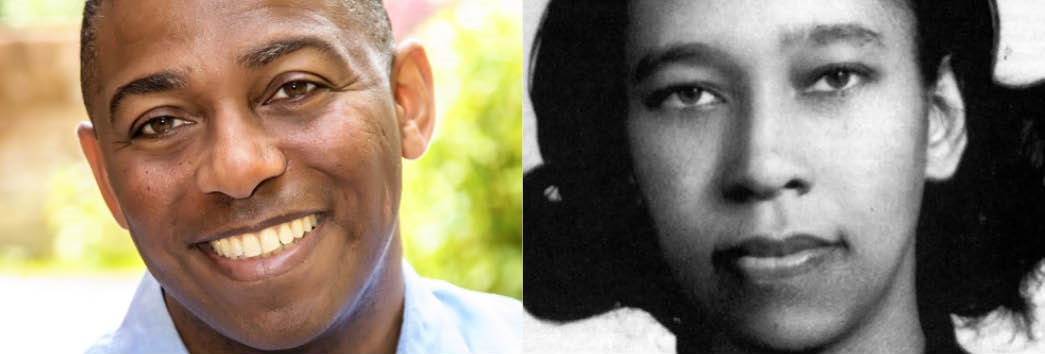

A few years ago, I began to research the work of composer Julia Perry. She was an American woman of colour who studied voice, piano, and composition and who during her lifetime managed to achieve what many composers wish for: having her works played by major orchestras – no mean feat in a world (especially in Western classical music) not designed for her. And yet, since her death at a tragically young age of 55, her name has fallen into near obscurity.

It’s 45 years since Julia Perry passed, having composed until the end despite a series of strokes which left her paralysed on her right side and confined to a wheelchair for the final nine years of her life. Determined to continue her work, she taught herself to use her left hand and did not stop working even after she was hospitalised. She faced down and broke through many barriers, and I’m confident she would be horrified to discover that the current generation of female composers and musicians are still having to fight just as hard for their place at music’s top table.

The stark warning about rampant misogyny in the music industry issued by the UK Government’s Women and Equalities Committee (WEC) late last month should give pause to us all. Female artists are routinely undervalued and undermined, the WEC concluded, and still have to work far harder ‘to get the recognition their ability merits’. The committee’s findings were somewhat echoed in a survey by UK charity Donne, Women in Music, which analysed the 2021-2022 concert repertoire of 111 worldwide orchestras and discovered only 7.7 percent of programmed work was by women, and a little over two percent was written by women of colour.

It’s a problem Julia Perry would no doubt have encountered; in fact, the industry’s inattention to the lack of a true meritocracy might even help to explain why the full impact of Perry’s work is yet to be realised.

In 2021, I was awarded an Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and BBC Radio 3 grant to celebrate the work of ethnically diverse composers from history, and I chose Perry: an underrepresented neoclassical/modernist composer with a later, more experimental body of work that to this day remains unpublished and unperformed. Part of my goal was to ‘explode the (classical music) canon to make room for more’, and though Perry was celebrated, published, and performed in her time, her success has not saved her from being largely forgotten nor a substantial number of her works from being lost or, worse still, destroyed.

Her story is fascinating on many levels. Perry was born in 1924 into a prominent family in segregated Lexington, Kentucky, but began her formal music training after relocating to Akron, Ohio. She went on to study at the Westminster Choir College, later winning two Guggenheim Fellowships and studying in Italy with Luigi Dallapiccola and at the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau, where she won the Prix Fontainebleau under the tutelage of one of the most formidable teachers of the 20th century – Nadia Boulanger.

She toured Europe, singing her Stabat Mater to very positive reviews (even in Italy), and she conducted and gave lectures in Europe for the US Information Service (including for one of the BBC orchestras). Later in life while adjusting to a new and substantial disability, she continued to compose, absorbing the experience of the civil rights movement and always echoing the musical influences of her childhood. And yet, without the work of (mainly female) musicologists, it’s likely she would have disappeared completely; it perhaps has not helped that, despite extensive digging, researchers continue to draw many blanks about her private life. Even her own tombstone incorrectly details her date of birth.

The best way to understand her, then, remains through exploration of and exposure to her work. It’s what I hope to achieve during Julia Perry In Focus, a week-long celebration taking place at the Royal Northern College of Music (RNCM) from 26 February until 1 March. A mix of public, online, and student events, the week revisits Julia’s work as living, modern compositions via new recordings and performances, and concludes with a concert from the BBC Philharmonic (which includes her Stabat Mater) at The Bridgewater Hall, on 2 March.

Joining me first to begin the discussion about her legacy on Monday 26 February are scholars Professor Louise Toppin (University of Michigan), Dr Samantha Ege (Southampton University), Dr Nate Holder (International Chair in Music Education, RNCM), soprano Nadine Benjamin MBE, and Professor Jennie Henley (Director of Programmes, RNCM), and following that our RNCM Research Forum considers our understanding of the African American and African diasporic art song (Wednesday 28 February). Admission to both events is free, with no ticket required to attend, and both can be watched live on the RNCM YouTube channel.

For a small ticket price, you can hear some of Perry’s work played live at the College – starting with Homunculus CF, performed by the RNCM Percussion Ensemble on Thursday 29 February (1.15pm, £2.50-£5 plus £1 booking fee), and then A Short Piece for Orchestra will feature in the RNCM Symphony Orchestra’s programme on Friday 1 March (7.30pm, £7.50-£15 plus £1 booking fee) after a pre-concert discussion (admission free, no ticket required).

23 February 2024