Performing ‘New Diamonds’

By now, conservatoires have a number of years of ‘canon battling’ under their belts, years during which they have actively wrestled with the problem that the repertory resounding through their four walls—and from there to the world beyond—tends to be confined to a rather small ‘canon’ of works. ‘Conservatoire inhabitants’, as well as their critical friends and foes, have raised questions as to why that is so (but much of the ideological underpinning remains to be pulled into wider public debates), whether it should remain so (at least in so far as that this core not be replaced but merely expanded) and what we should do about it. Collectively we have approached this last question through communal artistic and scholarly endeavours ranging from databases that list the mere existence of repertory to attempts at raising awareness among those involved in teaching and music-making from early music education to the professional sector. There is a lot more that needs to be done, but the ideas of excavation, exposure, re-assessment of performance modes that bring different musics to life, wider representation and choice are gathering momentum!

The Juilliard Review Alumni supplement, Winter 1957-8 (Note: the year given in the new item indicates the last full year of attendance in the school)

Performing something that is relatively unknown presents both wonderful opportunities as well as challenges. Pianist Chiara Lordi shared with me that she had not come across Perry’s music prior to being invited to perform Perry’s Prelude for Piano on 1 March during the Pre-Concert Discussion that is part of our Julia Perry In Focus week. And, in attempting to find out about Perry, she at first encountered a troubling dearth of material until she chanced upon a podcast that led her to various sites of information. Yet, by her own admission, this was a picture far less rich than anything she might encounter with more mainstream composers. Her quest had followed her initial work with ‘the notes’—the simple learning of physical motion to get the music under the fingers. The next step, then, was the discovery of Perry’s ‘sound world’ via—as Chiara explained— seeking out further scores, other performances of the Prelude and of other music by Perry, as well as wider information about the composer so as to establish frameworks that would allow her to penetrate the piece and its meanings.

What she found was a musically, intriguing mixture of not so much different styles but nods to styles, particularly from the world of jazz, which were combined with intimate classical pianism in, for instance, the inner voice leading and the opportunities Perry sets for colourful pedalling. Chiara began to understand the piece as a canvas of colours that are infused with momentary influences by other twentieth-century composers that Perry weaves into a larger, intricate musical trajectory. It was living with the music that allowed this journey of discovery to unfold slowly, bringing to light what in Chiara’s mind became ‘paintballs’ that morph, during contemplation, from a seemingly random arrangement into elaborate, suggestive shapes.

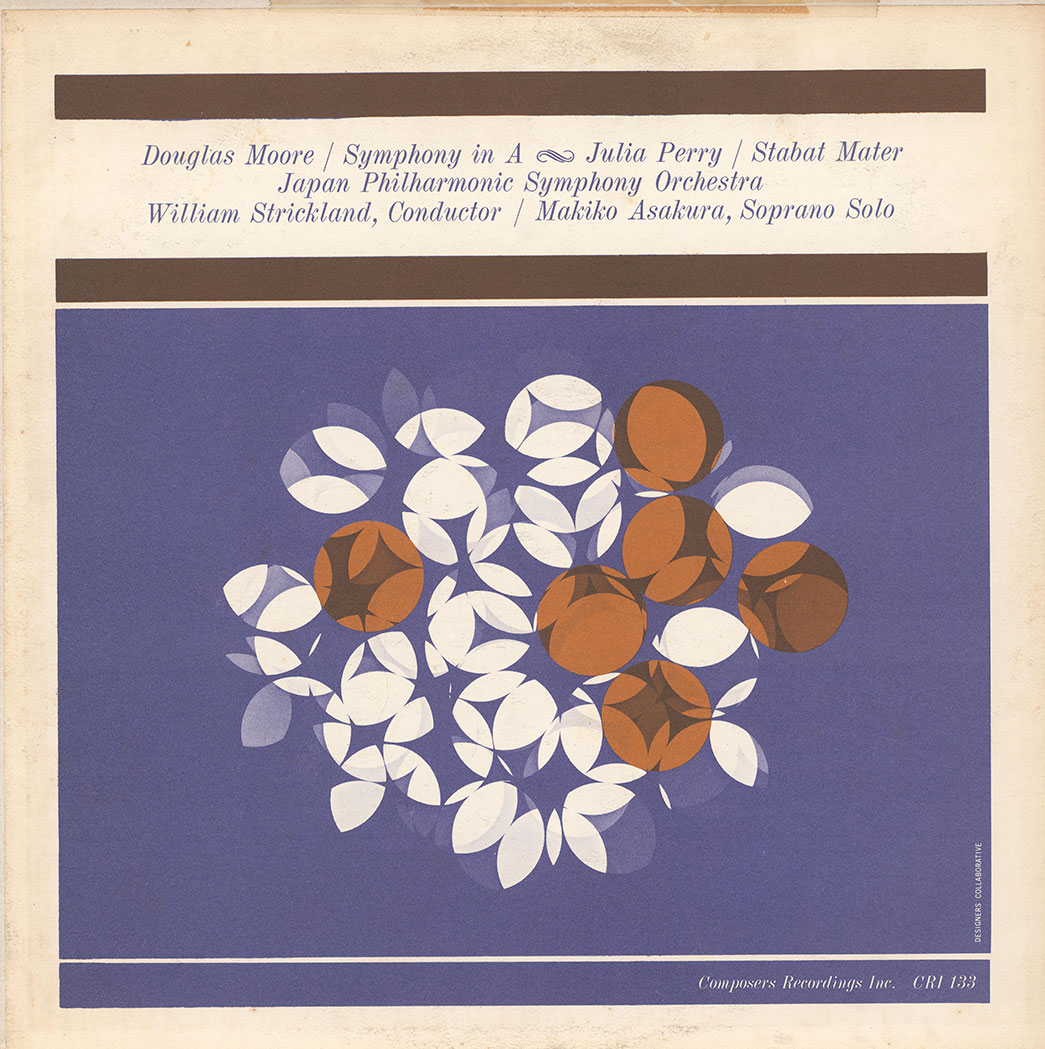

LP cover for the first recording of Julia Perry’s Stabat Mater (1960)

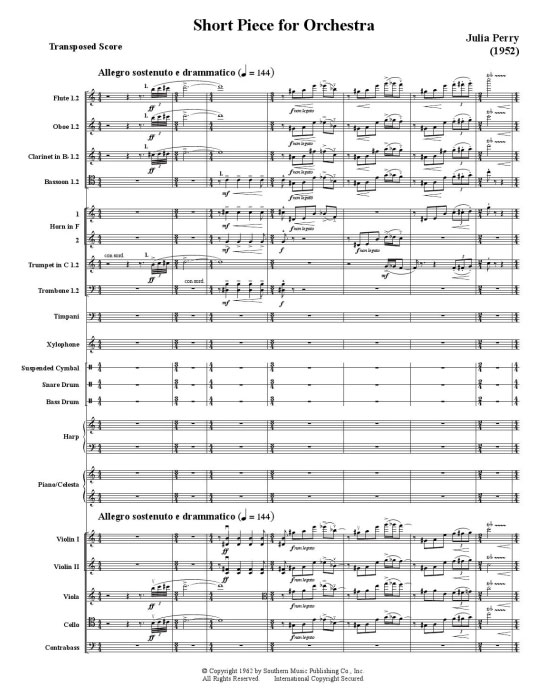

Conductor Jakub Przybycien described Perry’s Short Piece for Orchestra as a ‘drive through many landscapes’. To him, the piece is like the view from a car window that offers a rich tapestry of insinuations, some fleeting, some lingering a little longer, yet they are always embedded into the motion that carries you along to new places. He finds in her music many languages and colours that are all tied together by the strong presence of Perry’s own voice; not so much influences as momentary glimpses of the musical universe she herself experienced in her travels across the United States and Europe. At times, Jakub suggested, she merely carries with her the lingering scent of another’s perfume while rushing along her very own path. This faint sense of the familiar makes the new all the more exciting and, Jakub believes, allows any listener to find their own musical hooks that will embed it in their consciousness. He already has plans to programme the Short Piece for Orchestra— beyond the performance with the RNCM Symphony Orchestra during Julia Perry in Focus week. Jakub has discovered in it a most intriguing concert opener: an amuse-gueule that lasts long enough to have its own robust form and identity, yet is short enough to allow for the intrusion of quite strong spices without over-exercising the palate, calling on as it does an orchestra that is rich in instrumental colour while pragmatic in its size. Its hints of other styles lend it to pairing with any number of more familiar works which he sees as essential in expanding our repertory organically and with our audiences in mind. And these, Jakub suggests, should never be underestimated in their ability to grasp—knowingly or intuitively—when a composer has crafted out of the orchestra a diamond with just the perfect number of facets.

Wiebke Thormählen, RNCM Director of Research

1 March 2024