The Extraordinary Story of Hubert Harry

RNCM Archivist Heather Roberts investigates the life of Hubert Harry, a prodigious pianist listed as a soloist for the Matthay School of Music (later the Northern School of Music) by the time he was just nine years old.

Hubert later went on to study and teach in Switzerland, leaving a legacy of gratitude by his students and admiration from his peers.

Born in 1927 in Cumbria, his father gave him piano lessons when he was as young as three. His talent was soon apparent. He became a pupil of Hilda Collens herself, the founder and principal of the Northern School of Music, and progressed rapidly under her encouraging eye.

His debut as a soloist at nine years old inspired special mention in a review of the school’s performance in the Manchester Guardian: “Quite an astonishing performance on the pianoforte was that of a little boy of nine” who played with “imaginative insight”. The critic turns fortune teller when he writes, “it is possible on the strength of this early appearance to predict a bright future for him.”

Bright indeed! Just one slight snag though: the Second World War.

In 1945, just as the war is ending, Hubert turns 18. He was of age, healthy, fit, not employed in an essential role on the home front and therefore eligible for conscription. Even though the war itself was over, people were being called up until 1960. Just at the cusp of his career, an interruption like war service might have toppled it before it began.

Luckily, he had allies. Hilda Collens writes imploringly to the Lancashire local authority’s education committee to give him exemption, at least until he can take his final exams. Arguing that if he is called up, all the money they gave to sponsor his tuition would have been for naught. She writes to the authorities to try and stall his medical examination, essential in the conscription process.

It works. He is given exemption for a while to get his training completed and his performances gather recognition that he is “possessing musical gifts of no common order.”

That’s not all though. There are other tricks up the sleeves of his allies to ensure his musical training continues. He applies to continue his studies in the Lucerne Conservatoire. Lucerne in Switzerland… Switzerland that is a neutral country in the war… Switzerland where the British authorities can’t insist on his conscription. I see what you did there Hubert.

With glowing recommendations and obvious talent, he is accepted and off he goes.

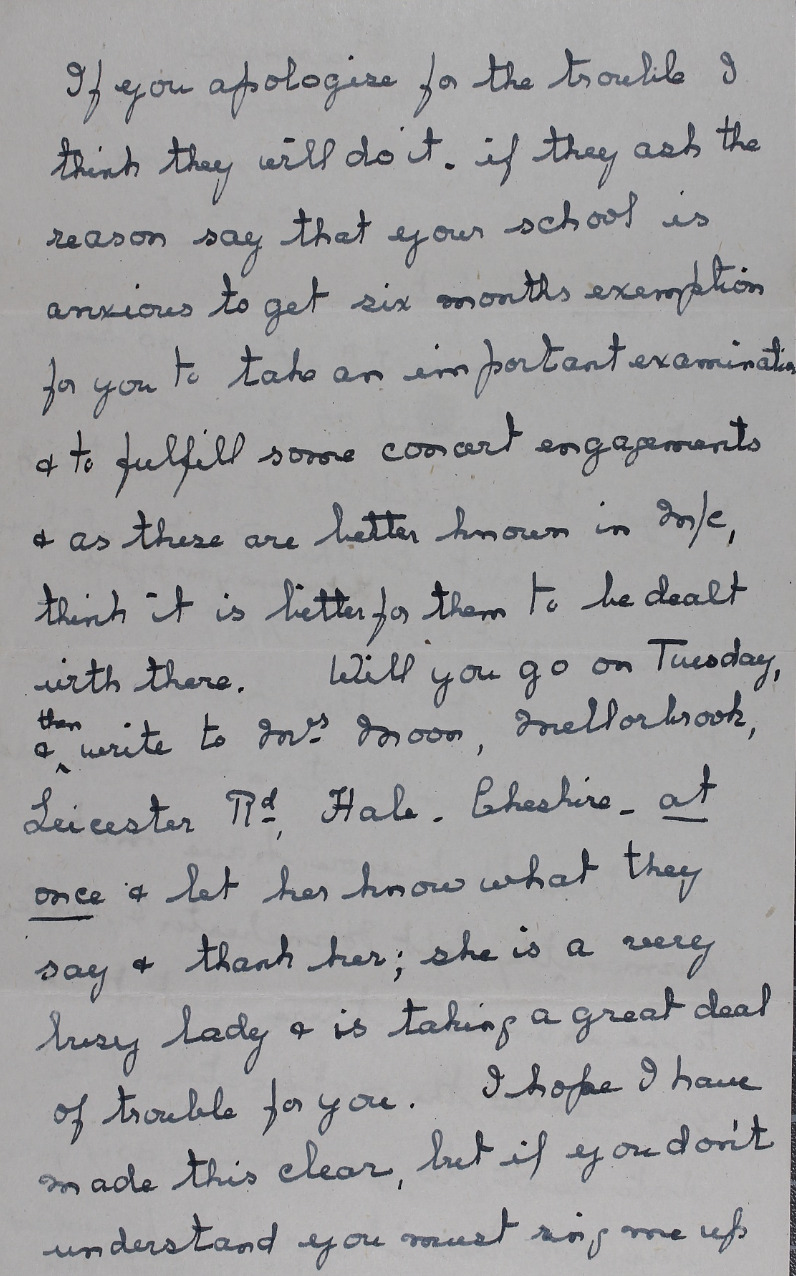

What happens then is documented in some of the loveliest archive records we have the pleasure of holding in the RNCM. He is sent letters by Hilda Collens until she dies in 1955. He never moves back to Britain and they keep up a correspondence as much as they can manage. Ida Carroll (secretary then principal of the Northern School of Music), Walter Carroll (her father and famous Manchester music educator) and Clifford Curzon (internationally renowned pianist and friend of the school), also keep their ties with Hubert through gorgeous handwritten correspondence.

What happens then is documented in some of the loveliest archive records we have the pleasure of holding in the RNCM. He is sent letters by Hilda Collens until she dies in 1955. He never moves back to Britain and they keep up a correspondence as much as they can manage. Ida Carroll (secretary then principal of the Northern School of Music), Walter Carroll (her father and famous Manchester music educator) and Clifford Curzon (internationally renowned pianist and friend of the school), also keep their ties with Hubert through gorgeous handwritten correspondence.

Hubert’s experience at Lucerne is mixed, given the advice that Hilda Collens seems prompted to share with him. He must work hard but most importantly, he must enjoy himself and not to worry if his playing doesn’t always achieve the standards he wishes as “I know it will come out right in the end”. He should listen to his tutors but also “learn from anyone who has anything to give you.” He must make sure he is performing and entering for competitions, but even if he loses he must “keep clear of petty jealousies and strife or they will inevitably affect your character and then your music.”

But most of all, for heaven’s sake he should not come back to Britain too soon. The second he’s back, Hilda seems convinced there will be agents of the government waiting to sign him up for war service and that will be the end of his career as a pianist. “So the alternative seems to be to stay out of England permanently or to get into the army as a pianist.”

He does come back occasionally to perform. In 1953, Hilda seems to change her tune, needling him that it’s time to play the newly restored Manchester Free Trade Hall since “it is high time you took a few risks.”

Hilda’s advice seems to have been taken as nuanced and contradictory as it sometimes appeared. He did enter competitions, even won accolades for a few, including the Geneva International Music Competition.

The influence, encouragement and loyalty of the relationship he held with the Northern School of Music and likewise that the school held with him, is evident in the 100+ letters. This makes them some of the most valuable records we hold about the school as they display the character of its teachings and the passion of its staff. If you’d like to explore them more, digitised images of all the letters are hosted by our friends at Manchester Digital Music Archive.

Do you remember the school? We would love to include your experiences in this legacy project. Please get in touch with our Archivist, Heather Roberts, for more information and ways to become involved.

[email protected] (0161-907-5211)

Explore our ongoing project exhibition with the Manchester Digital Music Archive here.

Supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund