Spreading Peanut Butter and Popping Popcorn: A Brief Introduction to Julia Perry’s Solo Piano Music

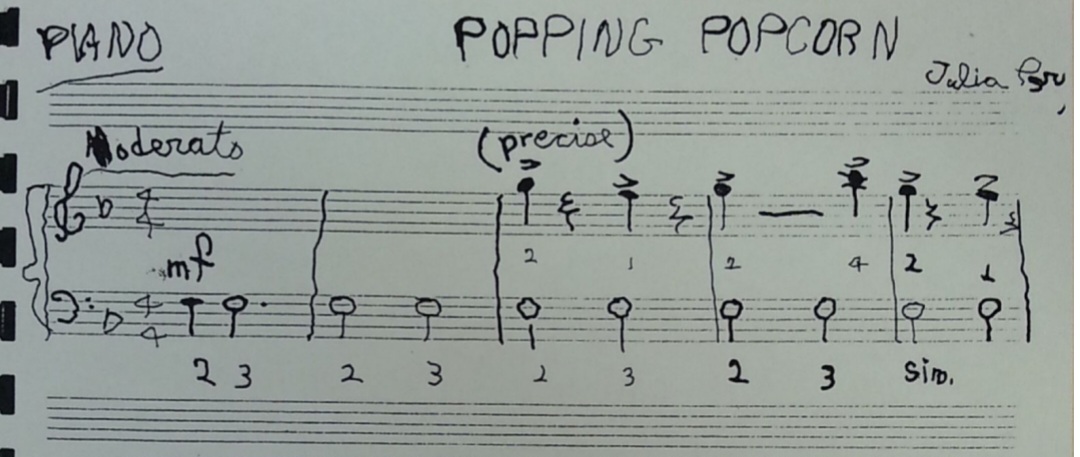

Although I’d already listened to both the Prelude for Solo Piano and the Miniature, what really drew me to Julia Perry’s solo piano music were the enticing subtitles of her Two Easy Piano Pieces (published in 1972)—who couldn’t resist at least a peak at a musical depiction of ‘spreading peanut butter’ or ‘popping popcorn’? I found the pieces online, and was intrigued…

Both works are extremely basic in the demands they make on the player, and they give the fingering for every single note. In Spreading Peanut Butter, the player’s hands never play together, and in Popping Popcorn, where they are used simultaneously, each has only one note at a time. Yes, these pieces were obviously written for children. The evidence of their publication date and, poignantly, of the shaky handwriting in both manuscripts, suggests that they were composed in, or slightly after, 1970, the year in which she had her first stroke. I’d like to think they were written with her own pupils in mind: one of her friends remembered seeing a sign in her apartment window advertising ‘Piano Lessons’ as early as the 1960s, and this was certainly one way she attempted to boost her income in her declining years.

Perry’s own musical education began in 1934, when she was 10 years old, and included singing, piano and violin. By the time she was in her Junior year at Westminster Choir College she had written at least three pieces for piano: the Prelude for Solo Piano, Pearls on Silk, and the intriguingly named Suite of Shoes. The first two, and a single movement of the third (‘Soldier’s Boots’) were performed in a concert given at the college on 26 May 1947. Sadly, Pearls and the Suite are among her many lost works. The Prelude fared better, despite it having had to wait until 1962 for publication, by which time Perry had revised it. Although the extent of the revisions is not known, the version we have today is very much in line with her other early works, showing the influences of spirituals and jazz, as well as pointing to the dense harmonies and short motivic cells that would come to characterise her mature style. I can’t find any evidence that her studies with Luigi Dallapicolla and Nadia Boulanger in the intervening years had any effect on her revision of the piece—but you can judge for yourself when student Chiara Lordi performs it at the Pre-concert Talk on Friday.

The only other piano piece currently available is the Miniature for Solo Piano, which was published in 1972, and shares its dependence on repeated non-melodic figuration with several of Perry’s works from the 1960s. This short, spare, toccata-like movement stands in sharp contrast to the expressive, blues-y feel of the early Prelude – yet both are instantly recognisable as the work of the same ‘too little known mid-century composer [who] defies pigeon-holing and stereotyping’ (Frank J. Oteri).

This small handful of solo piano music offers a tantalising taste of what future years may have in store as the Julia Perry Working Party and other researchers continue to explore archives and other sources of the composer’s music. In the meantime, however, and until my playing technique is a little more advanced, I’m going to have to content myself with Peanut Butter and Popcorn: not a bad combination, but definitely one that leaves me hungry for more!

Tonya Chirgwin

Library Assistant

RNCM

29 February 2024