Paris-Manchester 1918

Conservatoires in time of war

Keeping the Memory Alive

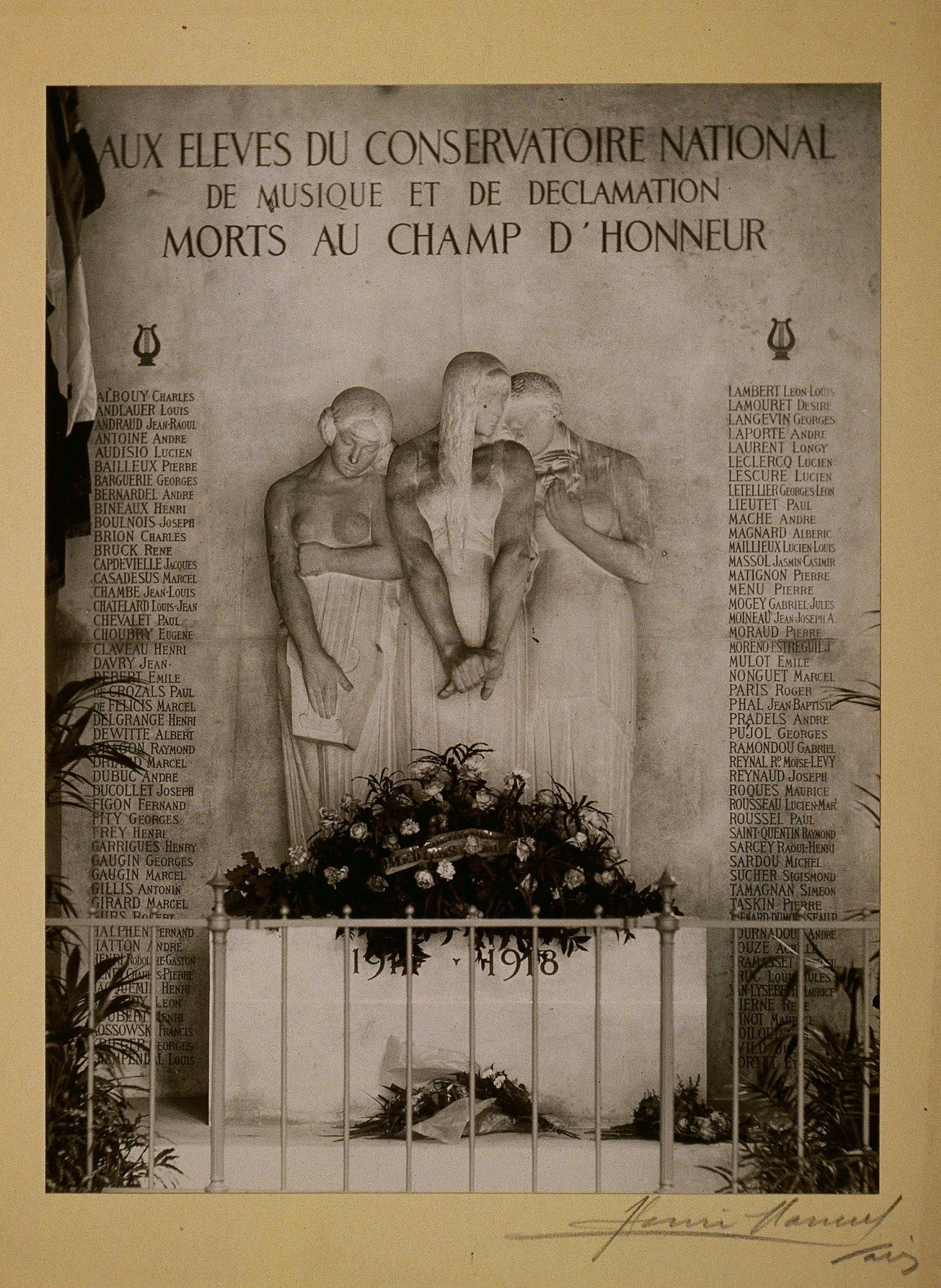

The Monument to the Dead of the Conservatoire was commissioned from the sculptor Pierre Lenoir (1879-1953) in 1919. It was erected in 1923 in the courtyard of the Conservatoire in the Rue de Madrid. Dismantled when the Conservatoire moved in 1991, the now dilapidated memorial is preserved in the historic monuments store.

Neoclassical in style, the group of women in high relief represents the two arts taught at the Conservatoire: music, with a lyre (on the left), and theatre, with a mask (on the right).[1] The central figure, lacking any attributes, is difficult to identify: she could be simply a mourner, or on the other hand a symbol of France or the Republic grieving for her children. Her posture (the lowered head, the hands, the hair undone and hanging down) is certainly consistent with the iconography of the mourner. Two lyres, Orphic symbols of music, are placed at the top of the list of names. These elements place this work in the category of monuments to members of communities or professional groups:[2] its purpose is to draw attention specifically to musicians (and, to a lesser extent, actors), in particular students from a single school: the Conservatoire.

Recent research on the musicians of the Conservatoire has allowed us to identify several students and graduates killed in action whose names were omitted from the monument. We may also note the inclusion of Albéric Magnard, who was indeed killed during a German assault on his home in the Oise but had not been called up. Nonetheless, his death, immediately portrayed as heroic by the press and in music circles in the opening days of the war, would continue to be a reminder of resistance to the “German invader” until the 1920s. For the death of Albéric Magnard, refer to the article by Patrice Marcilloux in La Grande Guerre des musiciens.[3]

Source

Henri Manuel (n.d.) : The Monument to the Dead of the Conservatoire 1914-1918

Paris: Museum of Music, E.995.6.238 B.

Document description: positive print

Catalogue: http://collectionsdumusee.philharmoniedeparis.fr/doc/MUSEE/0158117/monument-aux-morts-du-conservatoire-1914-1918-photographie

Bibliography

Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane and Prochasson, Christophe (2008) Sortir de la Grande Guerre. Le monde et l’après-1918, Paris: Tallandier.

Becker, Annette (1988) Les monuments aux morts. Mémoire de la Grande Guerre, Paris: Errance.

Becker, Annette (1994) La guerre et la foi, de la mort à la mémoire. 1914-1930, Paris: Armand Colin.

Becker, Annette (2001) “La Grande Guerre, entre mémoire et oubli”, Cahiers français, No. 303, July-August 2001.

Becker, Annette, Pelletier, Olivier, Renoux, Dominique, Rivé, Philippe and Thomas, Christophe (eds.), (1991) Monuments de mémoire, les monuments aux morts de la Grande Guerre, Paris: La Documentation française.

Bongrain, Anne, (2012) Le Conservatoire national de musique et de déclamation 1900-1930. Documents historiques et administratifs, Paris: Vrin.

Demiaux, Victor (2013) La construction rituelle de la victoire dans les capitales européennes après la Grande Guerre (Brussels, Bucharest, London, Paris, Rome), doctoral thesis, Paris: EHESS.

Hottin, Christian (2006) Le flambeau du savoir et la flamme du souvenir. Monuments aux morts et culte des morts dans les établissements d’enseignement supérieur (1918-1939), HAL open archives [on line at: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00010066].

Kosseleck, Reinhart (1997) « Les monuments aux morts, lieux de fondation de l’identité des survivants », in L’expérience de l’histoire, Paris: Gallimard, p. 135-160.

Prost, Antoine (1977) Les Anciens Combattants (1914-1939), Paris: Gallimard.

Scates, Bruce and Wheatley, Rebecca (2014) « Les monuments aux morts », in Winter, Jay (ed.) : La Grande Guerre, volume iii, Paris: Fayard, p. 563-598.

Tison, Stéphane, 2011: Comment sortir de la guerre ? Deuil, mémoire et traumatisme (1870-1940), Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes.

Winter, Jay (2008) Entre mémoire et deuil : la Grande Guerre dans l’histoire culturelle de l’Europe, Paris: Armand Colin.

Notes

[1]The first dance class (for girls) began in 1925. A dance class for boys was not offered until 1947.

[2]Christian Hottin (2006) Le flambeau du savoir et la flamme du souvenir. Monuments aux morts et culte des morts dans les établissements d’enseignement supérieur (1918-1939), HAL open archives [on line at: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00010066], p. 3.

[3]Patrice Marcilloux (2009) “La mort héroïsée d’Albéric Magnard: essai d’approche culturelle”, in Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau et al. (eds.), La Grande Guerre des musiciens, Lyon: Symétrie, p. 85-102.