Paris-Manchester 1918

Conservatoires in time of war

The Gazette des classes du Conservatoire (1915-1919)

Record of a Conservatoire at War

Although the Gazette des classes du Conservatoire came into being entirely at the initiative of Nadia (1887-1979) and Lili (1893-1918) Boulanger, it forms the most enduring record of a cultural institution – the Paris Conservatoire – at war.

A publication managed by two women

Daughters of the composer Ernest Boulanger (1815-1900), winner of the 1835 prix de Rome and voice teacher at the Conservatoire from 1872 to 1900,[1] and of the Russian princess Raïssa Mischetsky (1858-1935), Nadia and Lili Boulanger grew up in an environment where aristocrats, intellectuals and the Paris political elite mingled. Lili Boulanger’s victory in the 1913 prix de Rome – the first time that this prize for musical composition had ever been won by a woman for musical composition[2] – established the sisters’ reputation in French music circles[3] on the eve of the Great War.

After arriving at the Villa Medici in Rome on 12 March 1914,[4],[5] Lili Boulanger developed close relationships with the other residents. In addition to her friend Claude Delvincourt,[6] she struck up friendships with the architect Roger Séassal, the sculptors Armand Martial, Louis Lejeune and Lucienne Heuvelmans, and, above all, the architect Jacques Debat-Ponsan (1882-1942). However, her frail heath began to deteriorate. She therefore requested special permission from the Académie des beaux-arts to return to France[7] and departed on 1 July 1914.

The advent of the war left the two sisters feeling powerless. After concerts and theatrical performances ceased,[8]Lili, ill at the time, wrote: “I have completely taken new heart now, feeling the duty and the need to work.”[9] Taking refuge in Nice between 6 September and 7 November 1914, the sisters divided their time between rest, composition and helping the wounded at the Grand Hôtel de Nice, which had been converted into a military hospital.[10]

On their return to Nice, the sisters saw the promise of a quick war gradually fade as the soldiers found themselves bogged down in the mud of the first trenches. The only comfort for Lili was the exchange of letters with her friends Claude Delvincourt, Noël Gallon, Georges Caussade and Roger Séassal.

Birth of the Gazette and official recognition

Spurred on by an enthusiastic reaction from her close friends, Lili decided to expand her project to a larger group of recipients, with the help of her sister and their friend Jacques-Debat Ponsan. Through the influential Charles-Marie Widor[11] they met Whitney Warren, an internationally renowned American architect, member of the Beaux-arts Institute and ardent Francophile, to request his support.

Nadia and Lili’s idea was to establish a “gazette”, a regular publication featuring letters from classmates who had been called up, so that they could all exchange news.[12] The organisation responsible for this publication would be the “Franco-American Committee of the Conservatoire”, under the patronage of Whitney Warren. The composer Blair Fairchild was appointed treasurer, and Nadia and Lili the founding secretaries.

This new body easily found acceptance in French music circles. Gabriel Fauré, the director of the Conservatoire, was a family friend, as were most of the current teachers. With the exception of a reluctant Camille Saint-Saëns (who would eventually, and unenthusiastically, consent to being an honorary committee member), all of these – Gustave Charpentier, Théodore Dubois, Émile Paladhile, Paul Vidal and Charles-Marie Widor – responded enthusiastically.

Recreating the conditions of school friendships

Despite this heavyweight support, there were only four really active members of the Committee: Lili and Nadia Boulanger (of course), the faithful secretary Renée de Marquein, and Blair Fairchild, who had a great deal of experience as an administrator.[13] On 4 October 1915, the first “circular letter” was sent to classmates at the front and the rear, to ask them to write in to the Gazette regularly. This request received 51 responses, which would be published the following month.

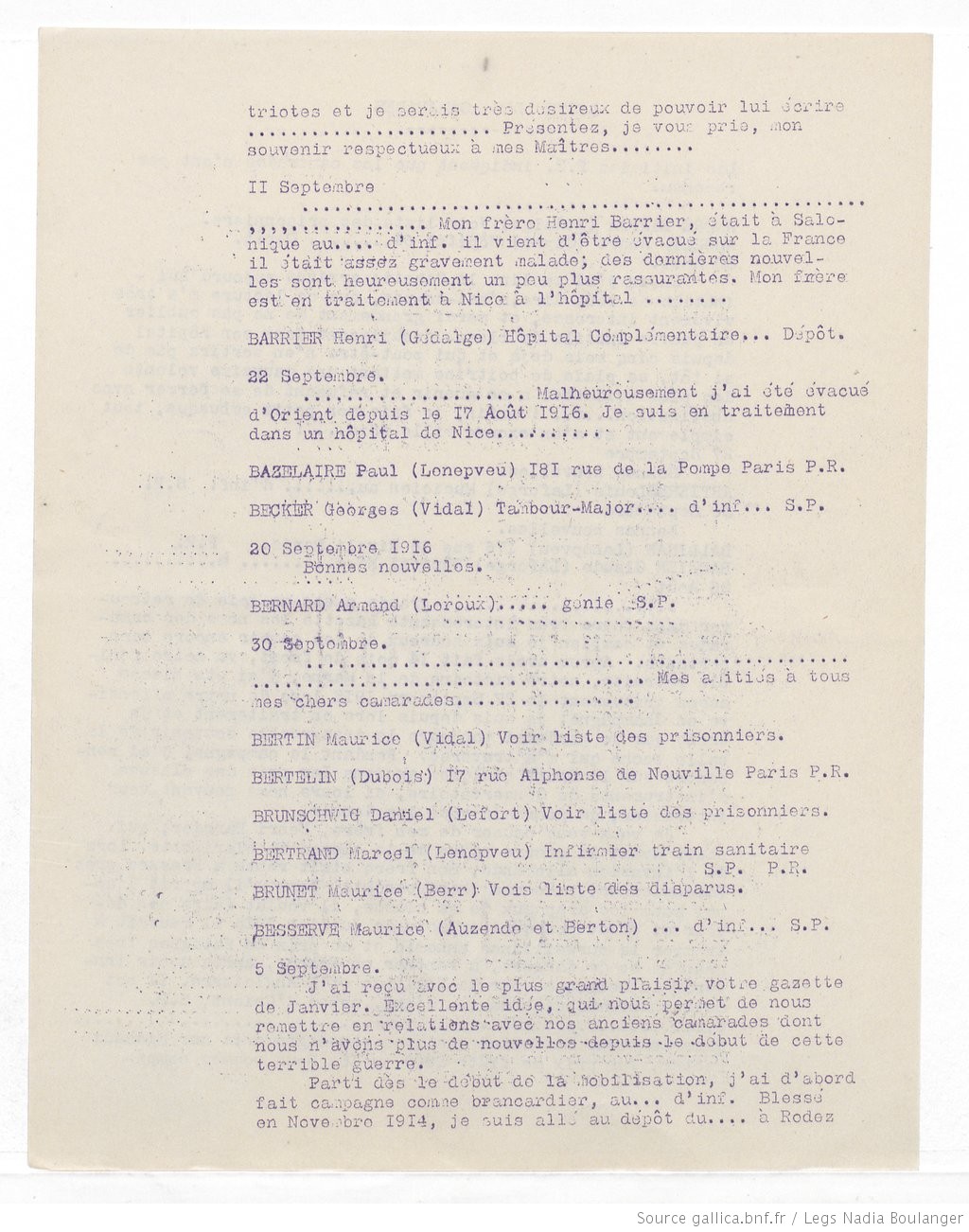

The Gazette was published on unbound sheets and laid out in the form of a list. Contributors appeared in (more or less) alphabetical order,[14] together with the names of those who had not responded. The texts of the letters are broken up by sets of full stops, indicating censorship imposed either by the Ministry or voluntarily carried out by the Committee.[15]

Franco-American Committee of the Conservatoire (1915) Gazette des classes de composition du Conservatoire, No. 1, Paris, November 1915, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Music Department, Rés Vm Dos 88 (1), cover page. View on Gallica

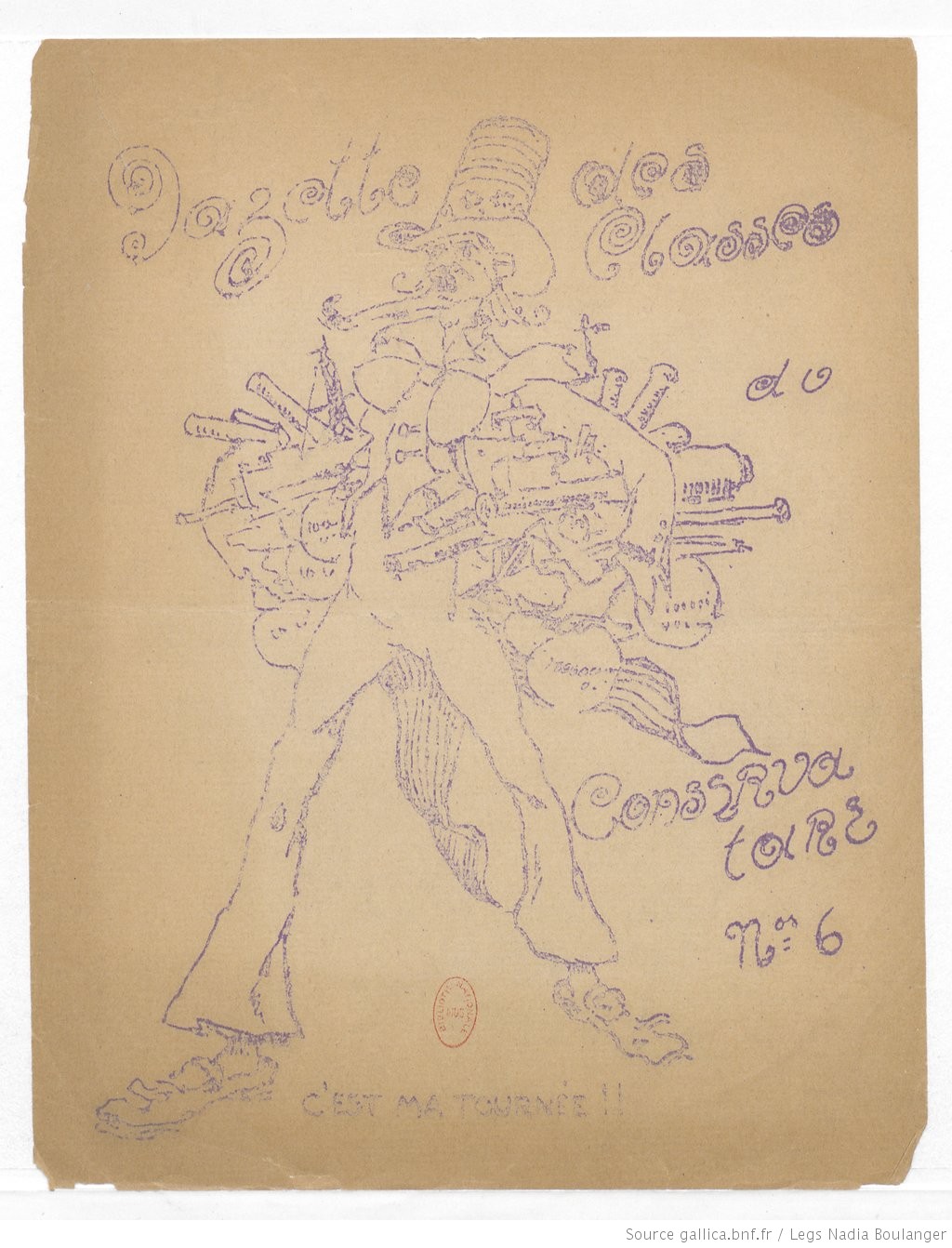

Gazette des classes du Conservatoire, No. 6, Paris, March 1917, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Music Department, Rés Vm Dos 88 (1), p. 45. View on Gallica

In gazettes 1 to 4 as well as issue 6 the letters are embellished with illustrations by Jacques Debat-Ponsan. Humorous in most cases, these drawings illustrate language that is at times colourful; occasionally they serve as comments on the content of a letter.

The publication was so successful that it continued until 1918, in spite of various difficulties and the death of Lili Boulanger in 1918. Truly a surrogate for the Conservatoire for those who had gone off to war, the Gazette, apart from news, provided the exchange of views and opinions on artistic topics.

316 students and graduates of the Conservatoire wrote to the Gazette, sending almost 1,600 letters that were until recently shut away in the archives of the Conservatoire and the Bibliothèque nationale de France. The handwritten letters for issue 12 are preserved in a box at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Never published, these letters are responses to the question: “What are your plans for after the war?” This seems like an invitation to turn over a new leaf . . .

Bibliography

Holland-Barry, Anya B. (2012) Lili Boulanger (1893–1918) and World War I France: Mobilizing Motherhood and the Good Suffering, doctoral thesis, Madison: University of Wisconsin [on line].

Laederich, Alexandra (ed.) (2007) Nadia et Lili Boulanger. Témoignages et études, Lyon: Symétrie.

Laederich, Alexandra (2009) “Nadia Boulanger et le Comité franco-américain du Conservatoire (1915-1919)”, in Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane et al. (eds.), La Grande Guerre des musiciens, Lyon: Symétrie, p. 161-174.

Mastin, David, 2016 : ‘“Aux Armes! Musiciens!” Les élèves du Conservatoire national en Grande Guerre’, Jardin, Étienne (ed.), Music and War in Europe from the French Revolution to WWI, Turhout: Brepols Publishers.

Rosentiel, Léonie, 1978: The Life and Works of Lili Boulanger, London: Associated University Press.

Segond-Genovesi, Charlotte, 2009: “De l’Union sacrée au Journal des débats: une lecture de la Gazette des classes du Conservatoire (1914-1918)”, in Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane et al. (ed.), La Grande Guerre des musiciens, Lyon: Symétrie, p. 175-190.

Segond-Genovesi, Charlotte, 2013: “Penser l’après-guerre: aspirations et réalisations dans le monde musical (1914-1918)”, in PONS, Lionel (ed.), Lucien Durosoir. Un compositeur moderne né romantique, Albi: Fraction, p. 5-39 [on line].

Spycket, Jérôme (2004) À la recherche de Lili Boulanger : essai biographique, Paris: Fayard.

Notes

[1]Constant, Pierre (1900) Le Conservatoire national de musique et de déclamation. Documents administratifs, Paris: Imprimerie nationale, p. 402.

[2]“Now, for the first time, the first Grand Prix de Rome for music has been awarded to a woman. This is a significant event. Thanks to Lily [sic] Boulanger, feminism has just won a victory that will be justly remembered. […] Admirably gifted, she undoubtedly has a brilliant musical career ahead of her.” (La Presse, 16 July 1913, p. 2, see on line).

[3]“Lili Boulanger, who has just won the Grand Prix de Rome with Faust et Hélène […] is only 19 years old . . . Her experience in the diverse ways of writing music is that of a person many years her senior!” (Claude Debussy (1913) “Concerts Colonne. – Société des nouveaux concerts”, Revue musicale S.I.M., 1st December 1913, Paris: Société internationale de musique, p. 44).

[4]Lili obtained permission on health grounds to delay her arrival at the Villa Medici.

[5]Diary of Lili Boulanger, 1914, unpublished, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Music Department, Rés Vmf ms 119.

[6]Claude Delvincourt (1888-1954) won the 1913 prix de Rome jointly with Lili Boulanger.

[7]Alexandra Laederich (2009) “Nadia Boulanger et le Comité franco-américain du Conservatoire (1915-1919)”, in Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane et al. (eds.), La Grande Guerre des musiciens, Lyon: Symétrie, p. 163.

[8]On 2 August 1914, the French government declared a state of emergency, which led to a ban on performances in theatres and live music cafés (Journal officiel, 3 August 1914, p. 7083).

[9]Lili Boulanger (1915) Letter to Miki Piré, 6 September 1915, unpublished, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Music Department, La Boulanger Lili 19.

[10]Diary of Lili Boulanger, 18 October 1914, unpublished, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Music Department, Rés Vmf ms 188

[11]The composer and organist Charles-Marie Widor (1844-1937) was a member of the Académie des Beaux-arts.

[12]This Gazette was in fact modelled on the “studio gazettes” produced by students at the École des beaux-arts. On this topic, see Frédérique Joannic-Seta (2015) “Les Gazettes d’ateliers de la Grande Guerre”, website of the Bibliothèque de documentation internationale contemporaine, (on line). Now digitised, the studio gazettes published during the Great War are available from the website of the Bibliothèque internationale de documentation contemporaine.

[13]Blair Fairchild, having graduated from Harvard, worked as a US embassy attaché in Tehran between 1901 and 1903.

[14]The only exceptions to the above layout are the 11th and 12th gazettes, which list the contributors by the date on which their letters were received.

[15]Comparison with thehand-written letters shows that the members of the Committee systematically redacted all personal information, in particular expressions of thanks to Nadia and Lili Boulanger.