Paris-Manchester 1918

Conservatoires in time of war

Resisting moral brutalisation

The violence of the war has a brutalising effect on men: deprived of everything and constantly in the presence of death, they gradually become like animals. In an attempt to hold on to their humanity, soldiers return to their pre-war culture: books and music are “elements of civilisation” that prevent them from sinking into the lunacy of violence. These elements of civilisation include classical texts (memories from school days?), painting and, of course, music. Together with two contemporary French composers (Debussy and Ravel), we note the name of Beethoven, one of the first German composers to be played again since the start of the conflict. This account seems like a statement of clarification, an occasion to renew with civilisation. It serves as an act of memory, inviting a feeling of melancholy.

Translation

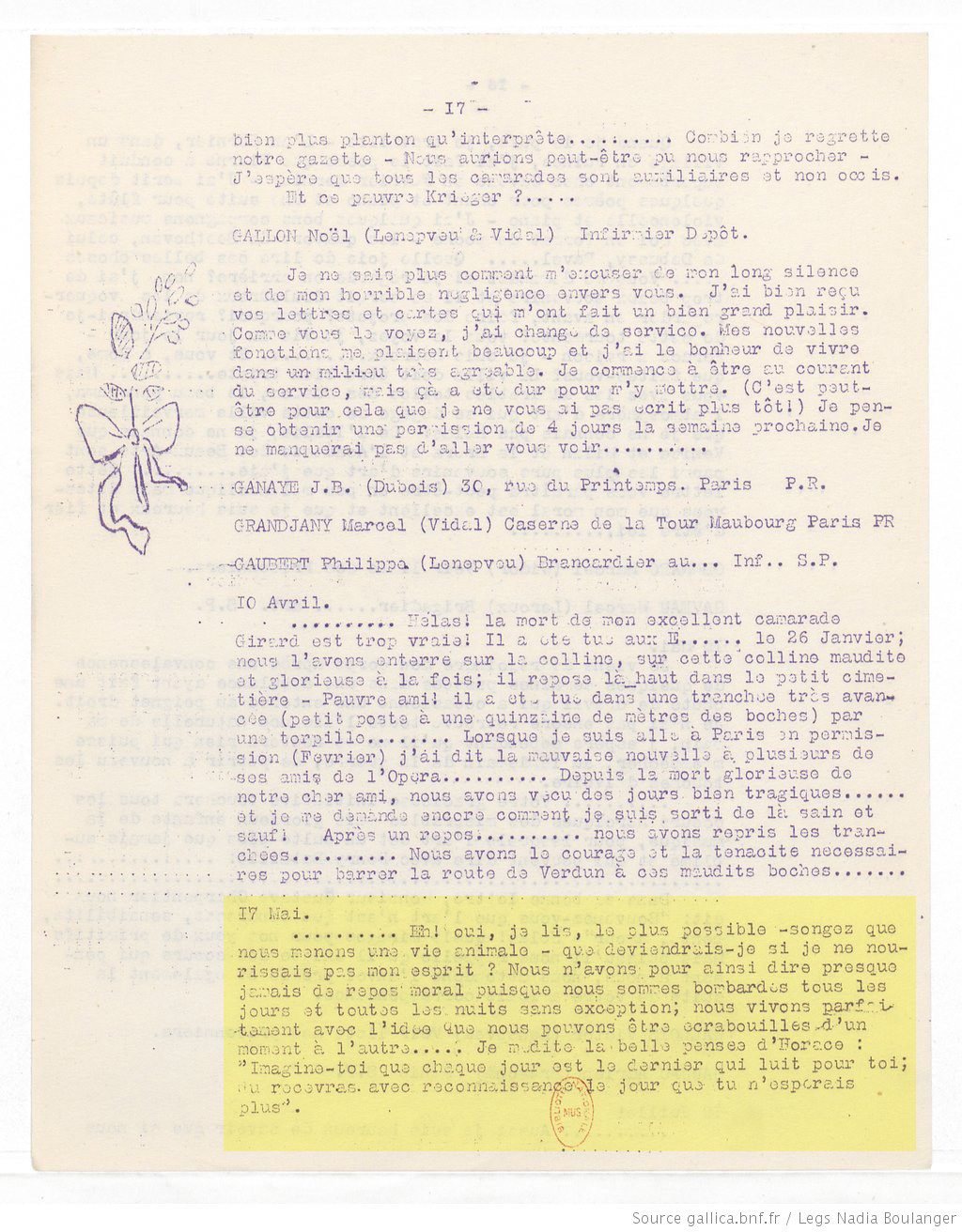

17 May.[1]

. . . . . . . . . . . . Yes, I do read, as much as possible. Remember that we live like animals – what would happen to me if I didn’t nourish my mind? We get almost no mental rest to speak of, since we are bombarded every day and every night without exception; we have accommodated ourselves perfectly to the idea that we could be crushed at any moment . . . . . I think about Horace’s fine saying: “Imagine that every day is your last; the hour to which you do not look forward will come as a welcome surprise”[2].

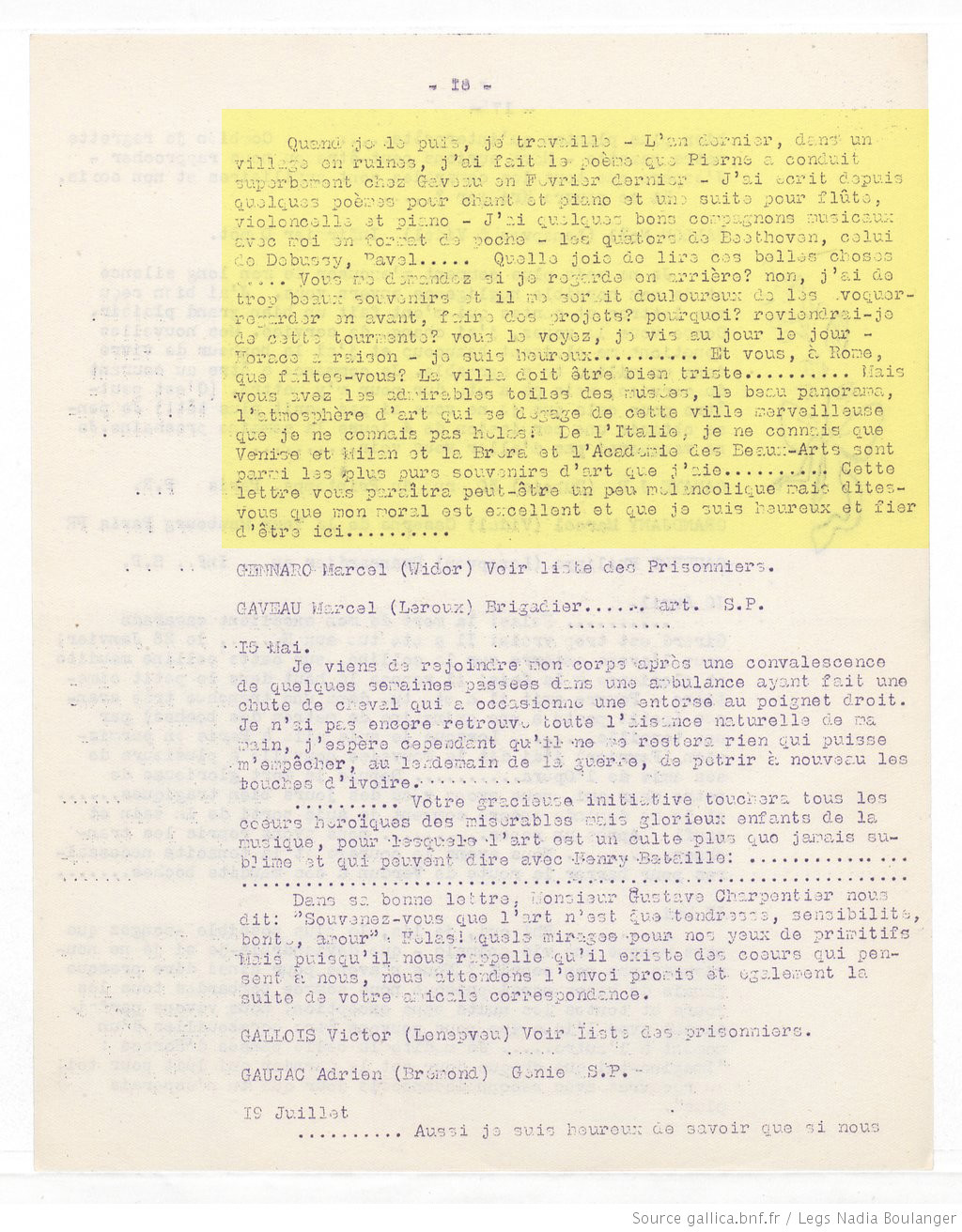

I work whenever I can. Last year, in a ruined village, I wrote the poem that Pierné[3] conducted superbly at the Salle Gaveau last February. I have since written some poems for voice and piano and a suite for flute, cello and piano.[4] I have some good pocket-sized musical friends with me – the string quartets of Beethoven as well as those by Debussy[5]and Ravel.[6] . . . What a pleasure to read these fine pieces. . . . . . You asked me if I look back. No, my memories are too beautiful , revisiting them would be painful. As for looking forward and making plans – why? Will I be coming back from this agony? As you can see, I’m living day by day – Horace is right – I am happy. . . . . . . And you – what are you doing in Rome?[7] That villa must be a sad place . . . . . . . . . . But you have the wonderful paintings in the museums, the fine view, the artistic atmosphere enveloping that wonderful city that I, unfortunately, do not know! The only places I do know in Italy are Venice and Milan, and the Brera[8] and Academy of Fine Art are among my purest memories of art. . . . . . . . . This letter might seem a bit melancholy to you, but please believe that I am in excellent spirits, and that I am happy and proud to be here . . . . . . . . . . . .

[1]1916.

[2]Horace (65 BC – 8 BC), Epistles, Book I, Epistle 4.

[3]Gabriel Pierné (1863-1937), organist, composer and conductor.

[4]This suite was to become the Trois aquarelles for flute (or violin), cello and piano, published in 1921.

[5]Claude Debussy (1860-1918).

[6]Maurice Ravel (1875-1937), also called up in May 1916.

[7]In spring 1916, Nadia et Lili Boulanger were in Rome, hoping that the climate would alleviate Lili’s suffering and temporarily keep her away from the war.

[8]The Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan.

Source

Philippe Gaubert, (17 May 1916) Letter to the Franco-American Committee, in: Gazette des classes du Conservatoire, No. 3, Paris, October 1916, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Music Department, Rés Vm Dos 88 (1), p. 17-18 [on line].

Document description: mimeographed document in violet ink, 21×27 cm.