Paris-Manchester 1918

Conservatoires in time of war

Training the nation’s musicians during World War I (Barbara L. Kelly)

Tradition and change at the Royal Manchester College of Music

This article explores the themes of rupture and continuity in the context of conservatoire training at the Royal Manchester College of Music. Periods of war are often treated as exceptional, and rightly so, but in terms of culture and artistic activity, this is often less clear-cut. This study of Manchester conservatoire training during the Great War is an outcome of the research project ‘Making Music in Manchester’, which was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council; it was a collaboration between the RNCM and community partners, Manchester Central Library and the Hallé concerts society.[1] I have chosen to focus on musical life and training at the Royal Manchester College of Music to see to what extent the war made a difference to musical life at the college. The first part of this study examines the RMCM in the years leading up to the Great War, taking particular not of the 21st anniversary celebrations in the region and examining the typical repertoire in college’s public performances, noting the performance of French, British and contemporary music. Part two focuses on the impact of war on student numbers, the male-female ratio, instruments played and any changes in repertoire, making comparisons with war-time musical life in Paris. The final section examines the post-war transition, its impact on the student ecology and the temporary presence of ex-servicemen at the RMCM.

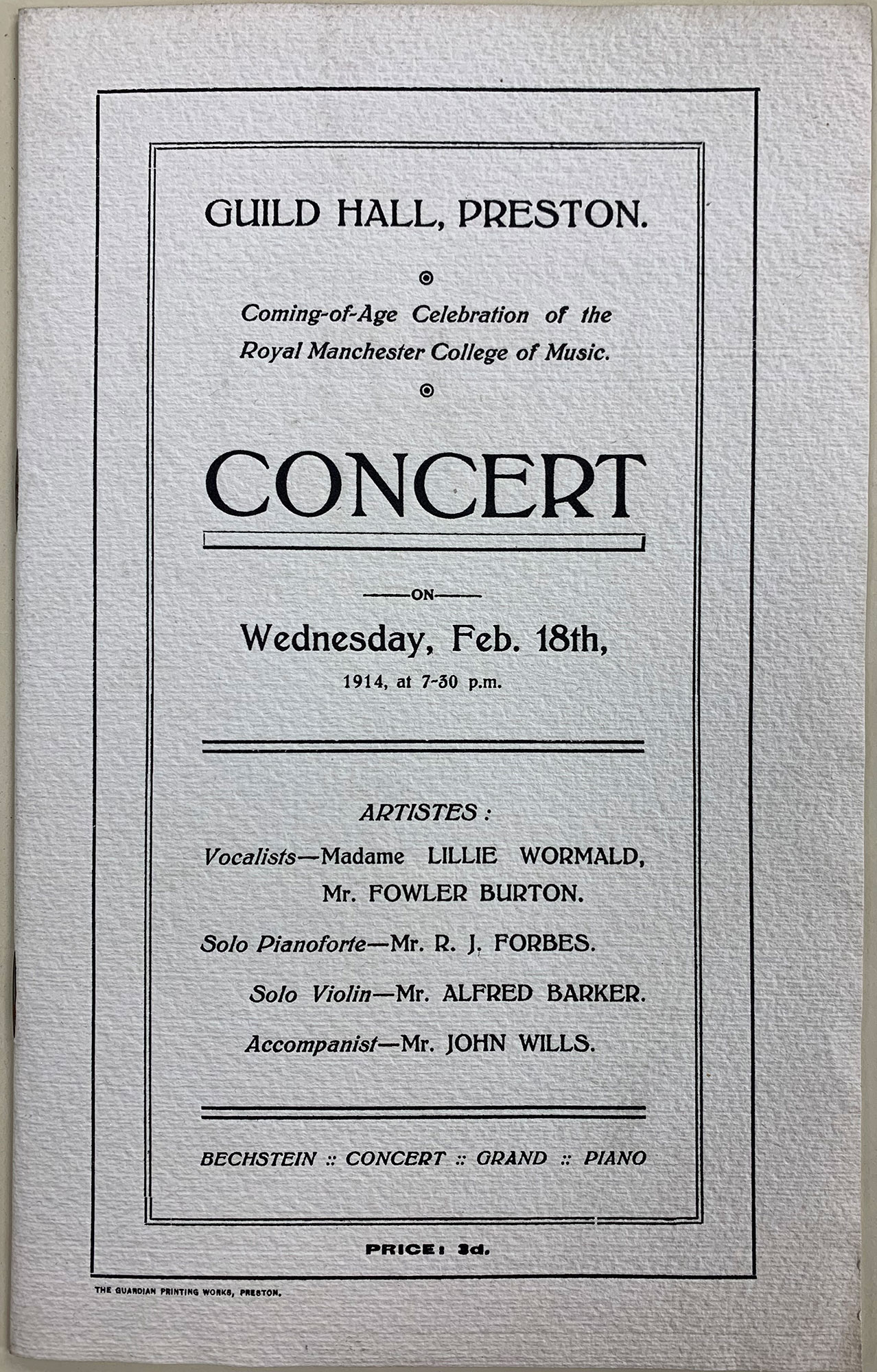

1914 was an important year at the Royal Manchester College of Music (RMCM); it was the college’s 21 birthday, which was described in all the publicity and reports as the RMCM’s ‘Coming of Age year’.[2] The planned celebrations reveal the college’s identity and mission to serve the north of England, particularly Lancashire and Cheshire. The celebrations took the form of series of concerts throughout the region with the purpose of drawing attention to the quality of training at the college for the purpose of publicity, but also the facilitate fundraising for local charities. In Bolton, for example, the surplice from the concert came to a total of £100 and benefitted the local Infirmary and Women’s Hostel.[3] The tour went to various towns in the North West of England, including Blackburn, Bolton, Burnley, Bury, Crewe, Leigh, Norwich, Preston, Rochdale and Stalybridge,[4] but it was cut short because of the outbreak of war in August 1814.

Since its foundation in 1893, the College has occupied a position in the forefront of musical progress in the North of England, from all parts of which its students have been drawn, and it is felt desirable that its coming of age should be the occasion for making its aims and work more widely known…The entire proceeds of the Concerts will, in every case, be devoted to the local charities of each town in which a concert is given.[5]

The concerts were performed by successful current and past students, including current students, Gertrude Barker and Frank Tipping and members of staff, such as R. J. Forbes, Arthur Catterall and Baynton Power. Figure 1 shows the Preston concert with works by Karl Goldmark, Brahms, Scottish traditional music, Handel, Chopin, Liszt, Tchaikovsky, Verdi, Sarasate, Franck, Debussy and Grenville Bantock

Figure 1: Preston Concert

There was an important new pre-war development with the introduction of a Department of Education with a new strand within the curriculum from 1910. According to the Annual Reports, it was very popular with external students and was regarded as an important pedagogic addition in recognition that the majority of students would pursue a career in teaching. Indeed, it also attracted a new cohort of musicians who were already teachers to its classes.[6] Secondly, the college’s awareness of recent European developments in the holistic training of musicians is evident from the introduction, in 1913 of Dalcroze eurythmics classes.[7] The minutes of the Meeting of Council of 26 February 1913 give approval for ‘experimental classes weekly in rhythmical gymnastics’ to take place the following term, taught by Dr T. Keighley.[8] The curtailed regional concert tour would have drawn attention to these important innovations, as well as showcasing the performance skills of it promising and successful current and former students.

Student Numbers 1910-1914

Figure 2: Student statistics 1910-1914[9]

| 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | |

| No. of students | 148 | 147 | 151 | 167 | 181 |

| Female/male | 96:52 | 97:50 | 98:53 | 117:50 | 126:55 |

| Age | 14 (-16)

68 (16-18 34 (18-19) 32 (21+) |

19 (-16)

63 (16-18) 33 (18-19) 32 (21+) |

20 (-16)

61 (16-18) 36 (18-19) 34 (21+) |

16 (-16)

74 (16-18) 50 (19-21) 27 (21+) |

18 (-16)

77 (16-18) 57 (19-21) 29 (21+) |

| Instruments | 34 singing

55 piano 38 violins 7 ‘cellos 2 double basses 1 flute 1 clarinet 1 trumpet 1 trombone 1 harp 5 organ 2 comp. |

47 singing

40 piano 41 violins 9 ‘cellos 2 double basses 1 flute 1 clarinet 1 trumpet 1 trombone 4 organ

|

50 singing

51 piano 32 violins 9 ‘cellos 2 double basses 1 flute 2 clarinets 1 trumpet 1 trombone 3 organ

|

62 singing

49 piano 36 violins 7 ‘cellos 1 double bass 2 flutes 1 oboe 3 clarinets 1 trumpet 1 trombone 3 organ 1 comp. |

66 singing

57 piano 38 violins 9 ‘cellos 1 flute 2 oboes 3 clarinets 1 French horn 1 trumpet 1 trombone 2 organ |

As Figure 2 shows, most students at the RMCM were singers, pianists and string players. There were very few wind instrument students in this period and during the war; this is in striking contrast to today, where the college has a reputation for solo and ensemble wind performance. There were wind and brass tutors on their books, such as Otto Schieder (bassoon), Franz Paersch (horn), J. Valk (trumpet), many of whom also played in the Hallé orchestra. In 1910 the college announced the appointment of a second tutor in clarinet, Mr H. Mortimer, because of a desire to increase student numbers. It also set up a £500 Scholarship in Wind Instrument playing ‘as being specially opportune and desirable for the furtherance of the work of the College in this important department’.[10] This is in contrast to French conservatoires, which had much higher numbers of wind players, who were almost entirely men. As David Mastin has shown, this became a huge problem in France during the First World War when most men suspended their studies to take part in the war effort.[11] The existing gender balance in favour of females at RMCM as well as the paucity of wind students in general, meant that they were protected from this issue. It was rather in the area of singers where the decrease in male students was more keenly felt. The 1915 annual report notes that ‘in consequence of the absence of nearly all the men singing students the opera with Miss Marie Brema hoped to produce at the close of the Session was given up’,[12] but work with the opera class continued with a range of ‘miscellaneous’ performances, including opera scenes from Saint-Saëns and Wagner, as we will see shortly. In 1917, Gluck’s Orpheus chorus was arranged for women’s voice by Dr Thomas Keighley.[13]

Repertoire: 1910-1914

There were four kinds of public concerts at the RMCM: Open Practice, Opera Scenes, Annual Public Examinations and professional chamber music concerts.

The Open Practice took place fortnightly; it was open to the public with a small charge to attend and it attracted large audiences. Opera scenes took place once/twice a year and attracted audiences and press reviews. There was a particularly notable performance of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneus just before the outbreak of war, in July 1914, which received positive reviews in the press, including The Times, but sparked a controversy with Sir Thomas Beecham. While the critic of The Times regarded it as the most ambitious operatic project to date, Beecham attacked the choice of opera as ‘archaic’ and wholly unsuitable for training students. The criticism was part of a larger debacle, in which Beecham addressed his criticism of Conservatoire training in Britain, and British singers, in particular, at an invited address to Council in December 1914, which spilled out into the pages of The Guardian with contributions by Stanley Withers (Acting Principal in Brodsky’s absence), Marie Brema (vocal tutor) and Edith Robinson (violin tutor).[14] The controversy led to a song contest to find a local singer capable of performing Delius’ Sea Drift. As Michael Kennedy asserts, it was won by Hamilton Harris, who helped to repair the reputational damage caused by Beecham’s assertions that British conservatoires were unable to produce highly skilled singers.[15] The incident revealed tensions about the purpose and role of conservatoires, the value of early and contemporary music, ‘English’ musical inferiority and a dose of wartime chauvinism. The performance of Purcell was exceptional; operatic scenes more usually drew on the core 19th century operatic tradition that Beecham recommended. The Vocal Department also organized elocution performances, for instance a Scenes from Shakespeare events in July 1916 and December 1917.[16]

The Annual Public Examinations took place in April and July and consisted of chamber, solo, vocal, and occasional orchestral performances eg, Symphonies of Beethoven, Mozart Concertos. They were open to the public and received press coverage from the Manchester Guardian, and they were regarded as a showcase for the college. The RMCM’s performance diary also included professional chamber concerts featuring internationally renowned staff, such as the Adolph Brodsky Quartet, Rawdon Briggs Quartet and all-female Edith Robinson Quartet. While the Brodsky Quartet upheld the Austro-Germanic classical tradition with additions from composers with whom Brodsky was close, the Edith Robinson Quartet was particularly active from the First World War onwards, gradually introducing new repertoire, including contemporary French music, as Geoff Thomason has shown in his thesis.[17]

Staples of the repertoire

The repertoire studied and performed by RMCM students during this period was largely typical of conservatoire practice in Britain and the continent. In terms of string repertoire, Bach, Beethoven, Brahms and Bruch featured prominently. Haydn, Mozart, Gluck, Handel, the latter particularly notable in the vocal repertoire, alongside Schubert and Schumann Lieder. The repertoire was firmly rooted in Austro-Germanic traditions, with some exceptions. Tchaikovsky and Franck were well established in the string and vocal repertory. Kreisler arrangements, Sarasate and Paganini enabled violinists to show their technical prowess. Other relatively recent repertoire included Grieg’s songs and piano works, with a performance of Grieg’s Piano Concerto on 6 July 1911. Liszt and Chopin constituted an important part of the piano repertoire. In addition to German Lieder, Italian operatic excerpts were common, alongside early music, particularly Purcell.

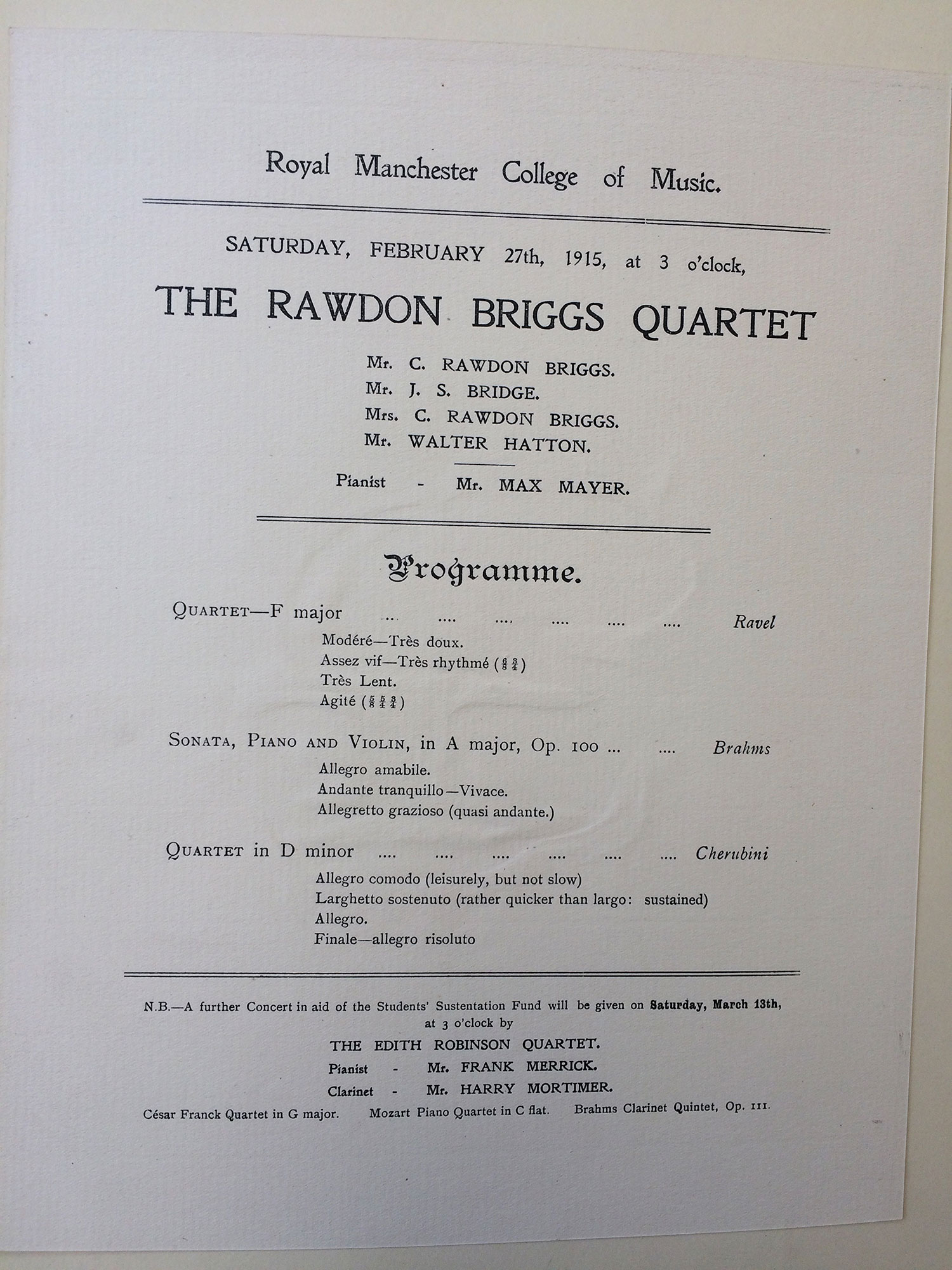

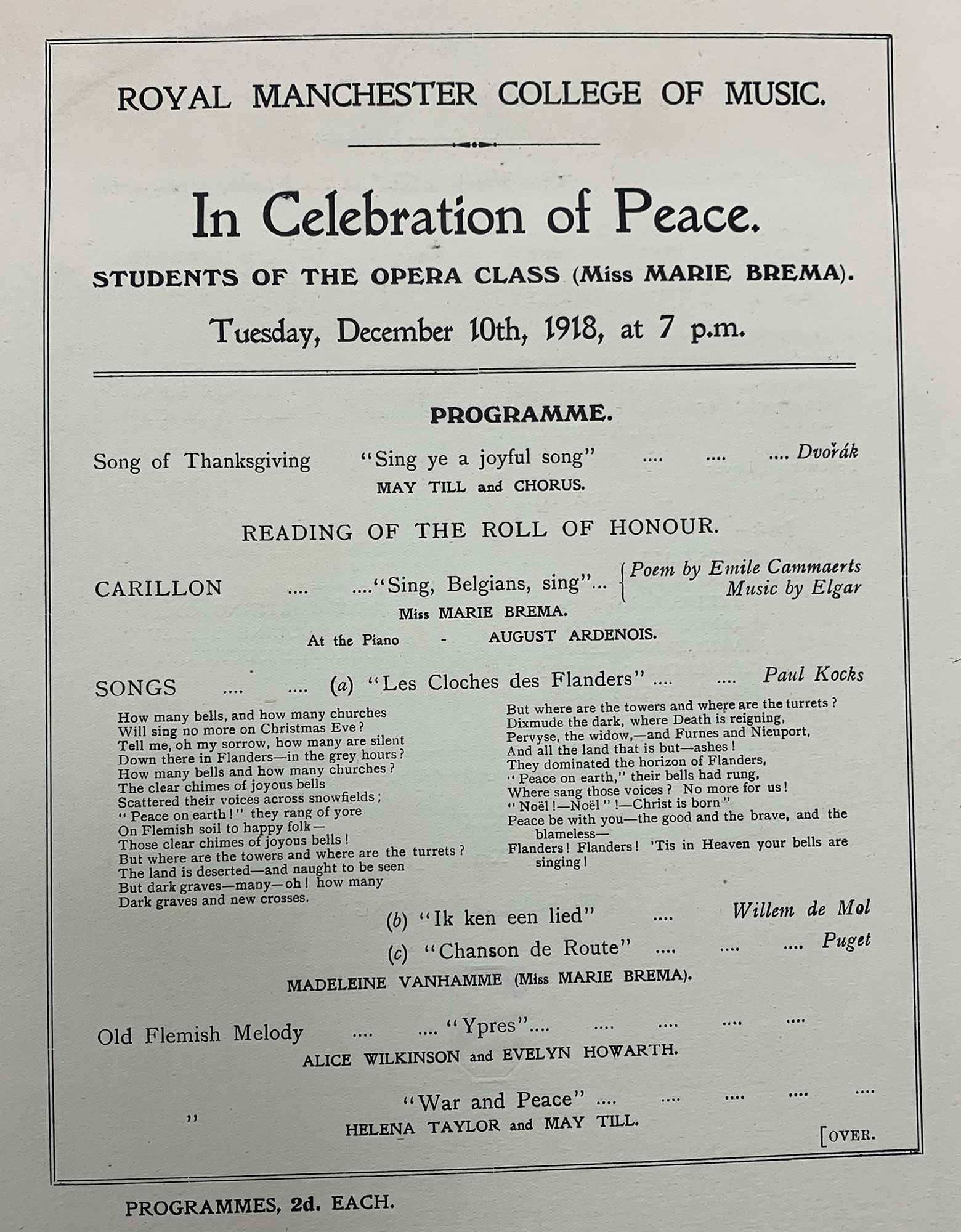

Turning to French repertoire, by 1914, Saint-Saëns, Vieuxtemps, Ambroise Thomas, Lalo (Symphonie Espagnole), De Beriot, Gounod, Widor and Guilmant (organ), Guilmant, Reynaldo Hahn (vocal) and Fauré songs provided a varied selection of 19th century French musical traditions. Most recent was the addition of Debussy piano works, ‘Jardins sous la pluie’, Estampes (1903) and ‘Reflets dans l’eau’, Images (first series, 1905), ‘Poissons d’or’, Images (second series, 1907) ‘, thanks to their introduction by RMCM piano tutors, Franck Merrick as early as 1907,[18] and also Max Mayer.[19] While recent French music was making its way to Manchester, it is perhaps more surprising that contemporary British music was not more plentiful in RMCM programmes. Elgar’s vocal music and Violin Concerto were performed, but given his national prominence, he hardly dominates. Grenville Bantock’s vocal works appeared in several programmes,[20] Samuel Coleridge-Taylor appears in a number of programmes shortly after his death in 1912, including the Northwich ‘Coming of Age Celebration of 3 February 1914, and Ralph Vaughan Williams was represented by vocal works from the Songs of Travel at the same concert (see Figure 4).

Figure 3: Programme of the Northwich ‘Coming of Age Celebration’, 3 February 1914

Unlike the Royal College of Music, the Royal Academy of Music and the Paris Conservatoire, the RMCM did not specialise in composition in this period. A few student composers are listed in the concerts, including H. Baynton-Power, String Octet in March 1911 and Alice Dill, part songs and a string quartet in 1911 too, but they are few and far between. The list of Principal Study specialisms in Figures 2 and 4, shows that only a handful of students took composition as their main area of study.

First World War

Figure 4: Student statistics 1915-1919[21]

| 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | |

| No. of students | 174 | 165 | 187 | 197 |

| Female/male | 131: 43 | 128: 37 | 153: 34 | 159: 38 |

| Age range | 17 (-16)

74 (16-18) 52 (19-21) 31 (21+) |

16 (-16)

71 (16-18) 49 (19-21) 29 (21+) |

18 (-16)

80 (16-18) 55 (19-21) 34 (21+) |

17 (-16)

82 (16-18) 61 (19-21) 37 (21+) |

| Instruments | 62 singing

59 piano 38 violins 5 cellos 1 flute 1 oboe 3 clarinets 1 French horn 4 organ |

54 singing

60 piano 34 violins 4 ‘cellos 1 flute 2 oboes 3 clarinets 1 French horn 6 organ |

60 singing

71 piano 37 violins 5 ‘cellos 2 oboes 4 clarinets 1 French horn 6 organ 1 comp. |

63 singing

72 piano 38 ‘cello 1 double bass 1 flute 2 oboes 4 clarinets 1 French horn 9 organ 1 comp. |

Wartime repertory:

The differences in repertoire during the war years were not as striking as one might expect. The mainstay of the repertoire was still Austro-German music, reflecting the taste and contacts of the Principal, Adolph Brodsky and other prominent teachers at the college. Tchaikovsky, Grieg, Ferruccio Busoni, Ottokar Nováček and Brahms feature on the staff and student programmes; as Geoff Thomason has shown, the Principal, the Russian violinist Adolph Brodsky introduced this repertoire, sometimes written for him and he invited some of the composers themselves to the college, showing his ability to maintain these high-profile European contacts and enrich the musical culture in Manchester.[22]

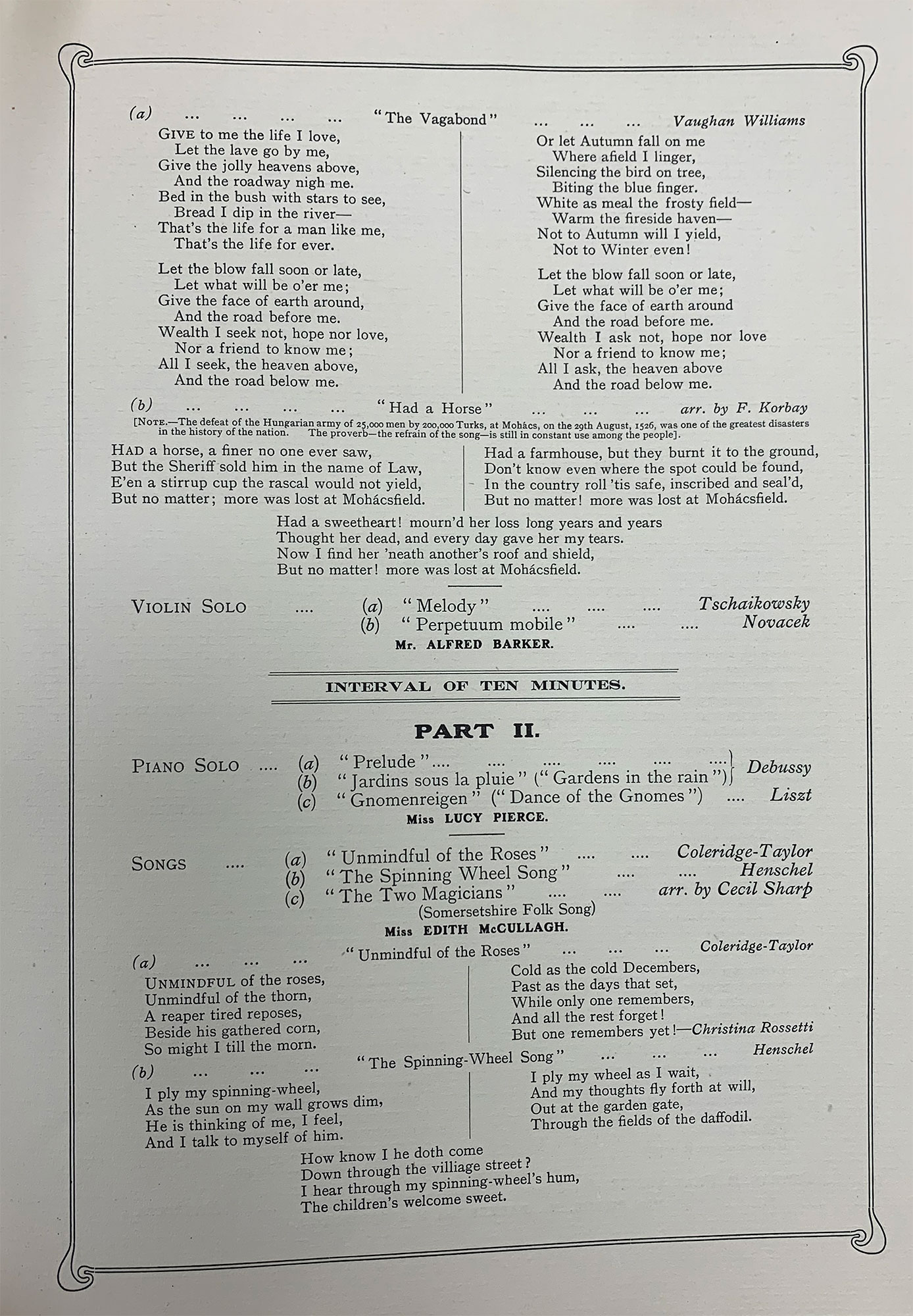

I have looked in some detail at the French repertoire that was performed during the war period. In many respects it is very similar to the pre-war period, with Saint-Saëns particularly prominent. Although not strictly French, César Franck is also a favourite, although this trails off a little as the war progresses. Students were familiar with composers such as Chabrier, Gounod, Fauré, Duparc, Chausson, Massenet and Bizet, to name a few. Debussy and Ravel become more prominent and are nearly always programmed by the piano tutor Robert J. Forbes, although the two composers’ songs start to make regular appearances. In addition to an increasing range of Debussy’s piano works, the Debussy’s Petite Suite was programmed on a number of occasions as a piano duet (including 31 March 1915), as well as the String Quartet and the very recent Sonata for Cello and Piano on 16 December 1916 and again on 17 March 1917[23]. Perhaps less likely was the vocal tutor’s interest in the early L’Enfant Prodigue, extracts of which were performed by her students on several occasions. Ravel too becomes more prominent, including his Quartet (Rawdon Briggs Quartet, 27 February 1915, shown in Figure 5), the famous Pavane, Sonatine, Jeux d’eau and finally the more recent Valses nobles et sentimentales (5 March 1918). The interest was clearly in late 19th and early 20th century French music. Berlioz made an appearance just once (the mélodie, ‘Absence’), and even Rameau and Couperin were absent, until the final victory concert, when the female vocal students performed the Prologue from Rameau’s Castor et Pollux (see Figure 6). Manchester’s often conservative conservatoire was reflecting the growing national interest in French music.

Figure 5: Ravel’s Quartet at the Rawdon Briggs Quartet concert, RMCM, 27 February 1915, RMCM E/1/5.

Figure 6: Celebration of Peace concert, RMCM, 10 December 1918, RMCM E/1/5.

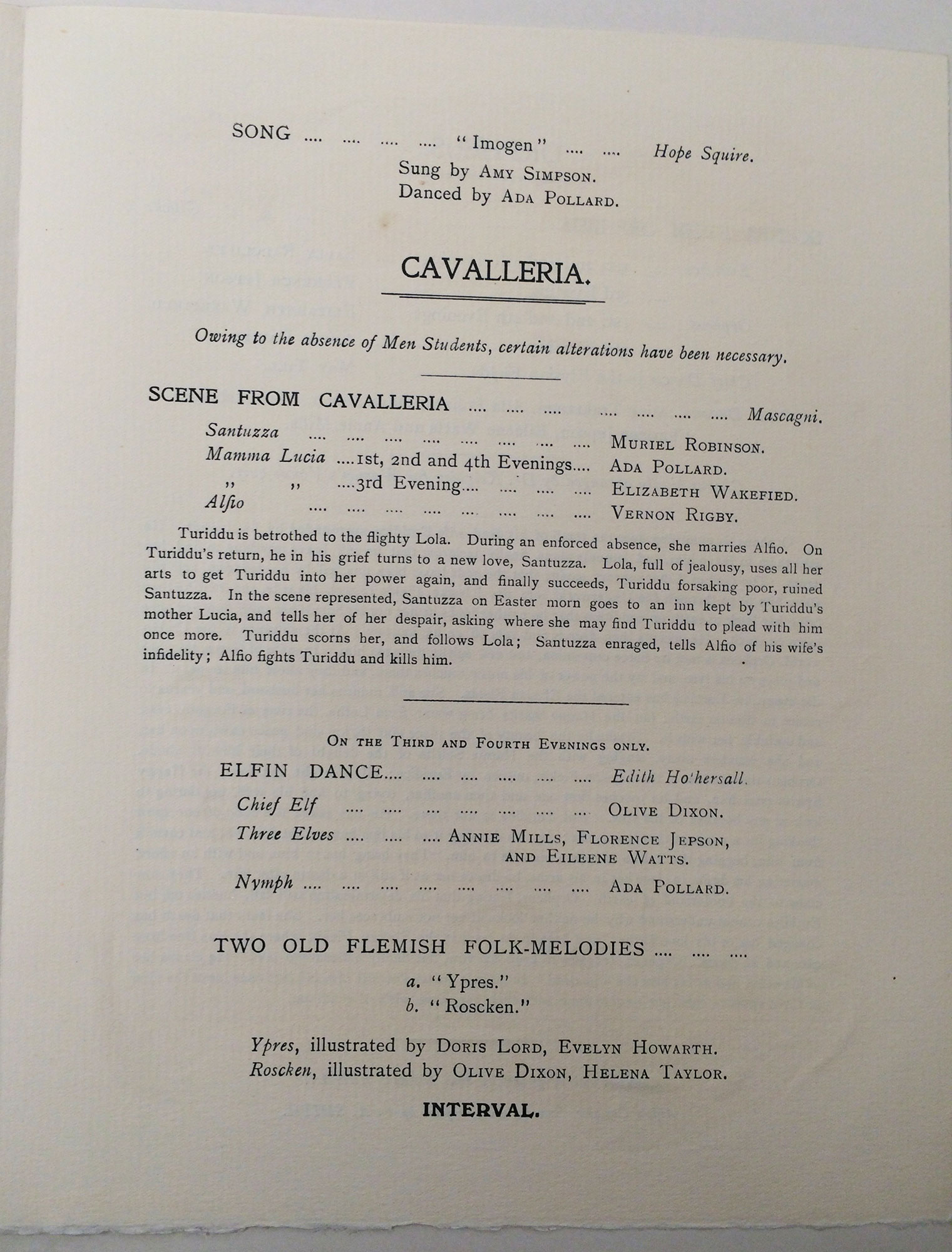

British music is still not prominent at the college. Purcell, Dowland, the adopted Handel, Thomas Weelkes, John Attey represent the small amount of early British music that was performed during the war, while more recent composers include Charles Villiers Stanford, Arthur Somervell and Frederick Delius; indeed, Stanford is by far the most frequently performed British composer at the start of the war, his place being gradually challenged by Delius. Despite Elgar’s national wartime status, there is remarkably little of his music programmed, beyond his songs during the war years; apart from the Sonata for ‘Cello and Piano, his other late works would have to wait until after his death to be heard at the RMCM.[24] A very few contemporary British composers received wartime performances at the college, in addition to the few students studying composition. These include Hope Squire, who took over her husband, Frank Merrick’s pupils when he was imprisoned as a Conscientious Objector.[25] Her song ‘Imogen’ was given in the context of Opera Scenes between 9 and 16 March 1917, alongside extracts from Gluck’s Orpheus, Wagner’s Lohengrin and Mascagni’s Cavalleria (See Figure 7).[26] The choral conductor, organist and composer, Sydney Nicholson’s Quintet for Piano and Strings was premiered by the Brodsky Quartet on 21 November 1918. Despite these few exceptions, in many respects, the college seems more remote from the national mood than the Hallé orchestra, as Eleanor Roberts shows in her presentation. The interim conductor, Sir Thomas Beecham, reflected his taste for the contemporary music of the Russian and French allies, introducing the city the most recent works by Debussy, Ravel and Stravinsky which had made such an impact in Paris and London.

Figure 7: extract from Opera Scenes programme, 9-16 March 1917, RMCM E/1/5.

One area in which the RMCM and Hallé were united was in their partiality for Wagner. Geoff Thomason traces this back to the vibrant German community in Manchester and the presence of prominent German musicians in Manchester, such as Charles Hallé, Hans Richter and German-trained Adolf Brodsky.[27] While the Hallé orchestra had established Wagner evenings before and during the war, at the RMCM, there are only arias from Tannhäuser in years preceding the Great War.

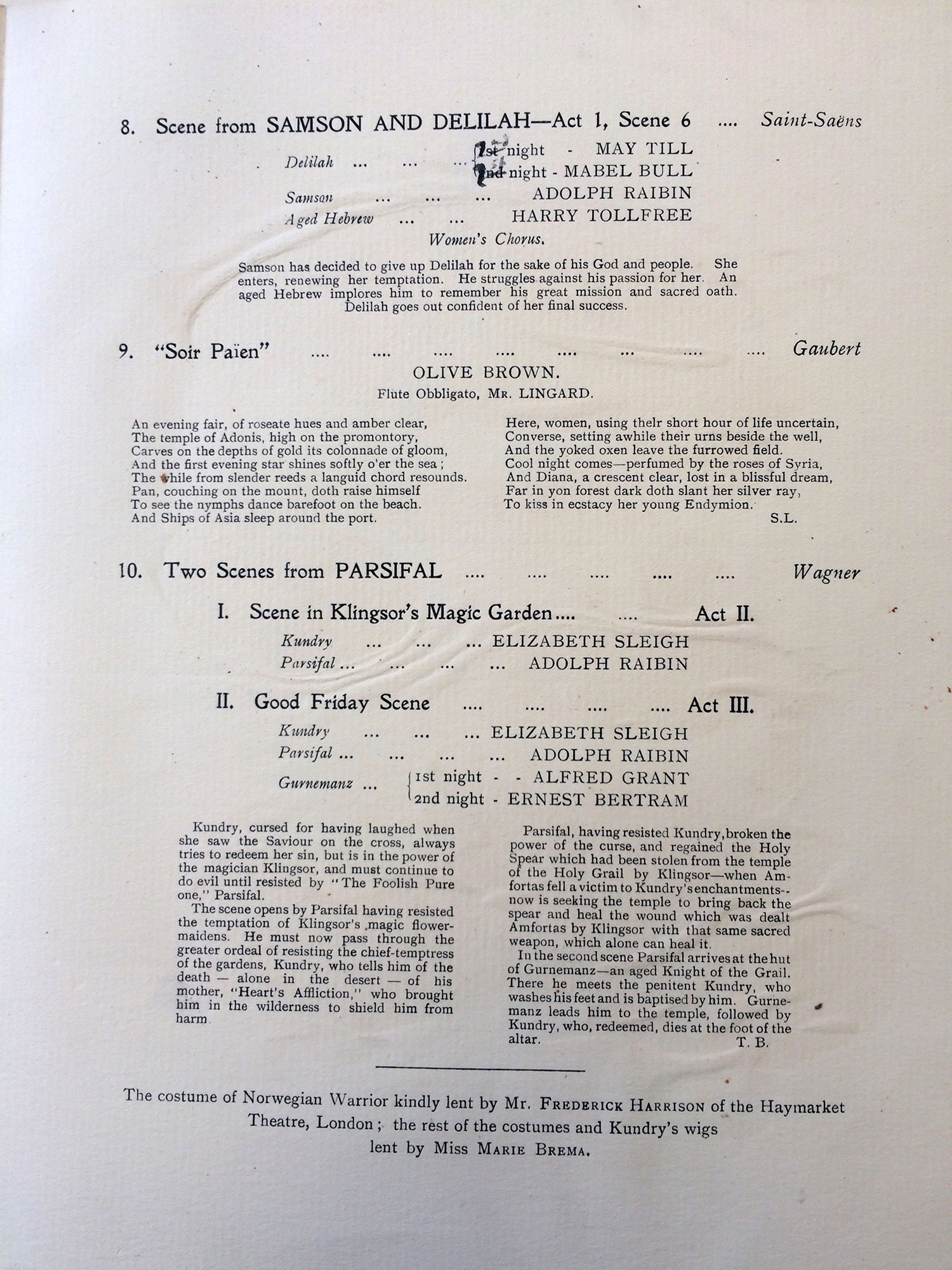

Wagner extracts of Tannhäuser, Meistersinger, Tristan, Lohengrin, Göttedämmerung and Parsifal were performed by the Vocal Studies students throughout the war period. The most symbolically significant event was the double bill of opera scenes from Saint-Saens’ Samson et Dalila and Wagner’s Parsifal on 14 and 15 July 1915 (See Figure 8). We know from the Annual Report that the choice was made because of the lack of male singers; they couldn’t put on a full opera. The choice is a striking one, particularly in a French context. Saint-Saëns was vociferous in campaigning in the press in a series of articles in the Echo de Paris to ban Wagner performances.[28] Wagner, who normally dominated French Colonne and Lamoureux concerts, was absent; in London too, Wagner was briefly removed from the concert programmes. This example shows that the particular national and regional context was crucial in deciding what was appropriate musically in times of war. The Hallé devoted many evenings entirely to Wagner. For others in London and Paris, this would have been seen as unpatriotic. Further removed from the action of war, it posed no problem in Manchester, due to the strong links many of the leading musicians in the city had with Austro-Germanic European musical traditions.

Figure 8: Extract of programme from Scenes from Samson et Delilah, and Parsifal, 14-15 July 1915, RMCM E/1/5.

Figure 8: Extract of programme from Scenes from Samson et Delilah, and Parsifal, 14-15 July 1915, RMCM E/1/5.

Impact of war on the college staff and students

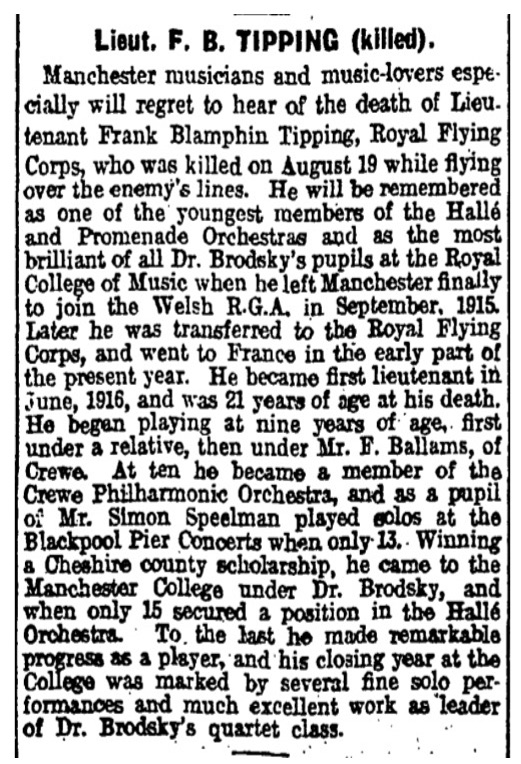

The college was affected by the war in a number of ways, although on a very different scale to the Paris Conservatoire: Adolph Brodsky was interned in Austria at the start of the war (returning in April 1915) and spent time in the Castle at Raabs, which was used as an Internment camp;[29] Carl Fuchs was held in Germany as a Prisoner of War, returning in April 1919;[30] Mr Hartford obtained a commission and became a Captain at the front; Frank Merrick (piano tutor) was held at Wormwood Scrubs prison as a Conscientious Objector and not released until the summer of 1919.[31] Many students signed up or got commissions, including Frank Tipping, who was a student of Brodsky’s; his death in 1917 marked the early end of a very promising career as a violinist.[32] His obituary in the Manchester Guardian comments that his loss will be especially felt by music lovers:

He will be remembered as one of the youngest members of the Hallé and Promenade Orchestras and as the most brilliant of all Dr. Brodsky’s pupils at the Royal [Manchester] College of Music … To the last he made remarkable progress as a player, and his closing year at the College was marked by several fine solo performances and much excellent work as leader of Dr. Brodsky’s quartet class. [33]

Figure 9: Obituary in the Manchester Guardian, 3 September 1917

There was a noticeable expansion in student numbers from the end of the war. The 1919 Annual Report notes ‘a progressive increase in the number of students… of both sexes’, which ‘placed a serious strain upon the accommodation of the College.’[34] In 1920, the student population had reached a point that the intake of new students had to be restricted with many placed on a ‘waiting list’.[35] The reason for this increase was the arrival of 88 ex-service men, who had been given Government grants to study music. While some had come through the Government Scheme for the Higher Education of Ex-Service students, a few had been sent by the Ministry of Labour and the War Pensions Committee. All were all given men (with one exception), and many would have been from less privileged social backgrounds than the usual RMCM student. Despite the assertion in the Annual Report that ‘The College has never refused admission to any ex-soldier who could satisfy the conditions of entry’, there is a sense of discomfort on the part of this sudden change in the college’s student body. Assurances are made that in no case can these students study for more than three years. It also notes that some had already withdrawn due to poor attendance or ‘an inability to conform to the conditions prescribed’.[36]

Nevertheless, the change in the musical ecology of the college took place slowly. Some of these scholarships were given to wind brass players and more research remains to be done to see what happened to these students. It brought about a change in the age-profile of the college and also in the social class mix of the students. However, the impact on the public performances is not really noticeable. The biggest increase is in the number of singers and pianists. There was also a very modest increase in number of wind and brass players. In 1923 we start to see the clarinet featuring in ensembles in college programmes.[37] The ex-servicemen and one woman blended into the college and were largely hidden from public view; according to the ‘Special Report’ in 1923, there was only one of these students left.[38] The student numbers indicate that the college underwent a considerable expansion from 165 in 1916 to 350 in 1919 and 405 in 1922 as Figures 4 and 10 show.

Figure 10: Student statistics 1920-23[39]

| 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | |

| No. of students | 228 | 350 | 360 | 405 | 384 |

| Female/male | 186: 42 | 220: 130 | 236: 124 | 265: 140 | 272: 112 |

| Age | 20 (-16)

81 (16-18) 82 (19-21) 45 (21+) |

No age profile given. | No age profile given. | No age profile given. | No age profile given. |

| Instruments | 73 singing

87 piano 41 violins 9 ‘cellos 1 double bass 2 flutes, 3 clarinets 10 organ 2 comp. |

115 singing

127 piano 54 violins 19 ‘cellos 3 flute 1 oboe 3 clarinets 1 bassoon 3 French horns 1 trumpet 1 trombone 1 timpani 15 organ 6 comp. |

110 singing

144 piano 53 violins 20 ‘cellos 2 oboes 2 clarinets 1 bassoon 2 French horns 2 trumpet 1 trombone 14 organ 5 comp.

|

125 singing

162 piano 57 violins 24 ‘cellos 5 flutes 2 oboes 3 clarinets 1 bassoon 4 French horns 2 trumpets 1 trombone 14 organ 5 comp. |

115 singing

167 piano 54 violins 18 ‘cellos 1 flute 1 oboe 5 clarinets 1 bassoon 1 French horn 1 trumpet 1 trombone 15 organ 4 comp.

|

Conclusions:

RMCM was protected from some of the disruption caused by the war in terms of its student body. The disruption that happened was gradually felt, as one of the Annual Reports asserts:

The Council, in presenting their Second War Report, are glad to be able to record a year of satisfactory work all things considered. This is largely due to the fact that women students have always preponderated and that the withdrawal of nearly all the men students for war work has been gradual since the summer of 1914.[40]

The college had, however, students and staff who were absent for various war-related reasons. Furthermore, in terms of repertory, it did not change in any dramatic way. Thomason’s research shows that the war marked the beginning of a change of musical priorities and focus in Manchester. The city wouldn’t be quite the same despite most of the musical men returning. Unlike France, it did not experience a shortage of wind players because it had so few from the start. Vocal music was most affected, and it is fascinating that the RMCM should favour Wagner at this historical moment, when other cities, notably Paris were avoiding his music. Contemporary French music was also gaining ground and, in this respect, the college and the city reflected a national musical orientation towards France.[41] The post-war period saw a change in the ecology of the college thanks to a recognition that music provided a suitable training for servicemen returning from the horrors of the Front. In addition, in 1922 a rival music college opened in the city, the Northern College of Music, which had a strong mission to train music teachers. But this post-war context is the subject of a future article.

Barbara L. Kelly, RNCM

[1] This paper was given at ‘Les Institutions musicales à Paris et à Manchester durant la Première Guerre mondiale’ conference, Paris Conservatoire, 5-6 March 2018.

[2] See ‘Special Celebrations Report’, Twenty-First Annual Report of Council, 1914, RMCM/B/3/3, pp. 10-16.

[3] Special Celebrations Report’, p. 15.

[4] See ‘Special Celebrations Report’, p. 14.

[5] See concert programmes, for example, ‘Coming of Age Celebration of the Royal Manchester College of Music’, Concert, Tuesday 3 February 1914, Congregational Lecture Hall, Northwich; ‘Coming of Age Celebrations of the Royal Manchester College of Music’, Concert, Wednesday 18 February, Guild Hall, Preston; ‘Coming-of-Age Celebrations, Concert, Monday 23 February 1914, Town Hall, Blackburn, Concert Programmes, RMCM E/1/4.

[6] See Seventeenth Annual Report of Council, 1910, ‘Annual Report’, p. 13; Twentieth Annual Report of Council, 1913, p. 10. RMCM/B/3/2.

[7] Twentieth Annual Report of Council, 1913, p. 10. RMCM/B/3/2. The RNCM has maintained its reputation for teaching Dalcroze to the current day. See Michael Kennedy, The History of the Royal Manchester College of Music (Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 1971), pp. 40-41.

[8] Royal Manchester College of Music, Meeting of Council, 26 February 1913, RMCM/C/1/2.

[9] Royal Manchester College of Music, Annual Report of Council, RMCM/B/3/2, 1910, p. 10; 1911, p. 10; 1912, p. 9; 1913, p. 11-12; RMCM/B/3/3, 1914, pp. 20-21.

[10] Seventeenth Annual Report of Council, 1910, ‘Annual Report’, p. 12, RMCM/B/3/2.

[11] David Mastin, ‘Écoles de musique en Grande Guerre’, Université Paris Ouest Nanterre-La Défense, unpublished PhD thesis, 2012.

[12] Twenty-second Annual Report of Council, 1915, pp. 15-16

[13] Scenes from Lohengrin, Cavalleria, and Orpheus, 9-16 March 1917, RMCM Concert Programmes, RMCM E/1/5.

[14] Thomas Beecham, ‘The Prospects of British Music. ‘Expulsion of Accomplished Foreigners’, The Manchester Guardian, 5 December 1914, p. 10; Thomas Beecham and George A. MacMillan, ‘Music and the Manchester College, Mr Thomas Beecham Returns to the Attack’, The Manchester Guardian, 11 December 1914, p. 12.

[15] For a fuller discussion, see Michael Kennedy, The History of the Royal Manchester College of Music (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1971), pp. 53-59.

[16] Concert Programmes, RMCM E/1/5.

[17] Geoff Thomason: ‘Brodsky and his circle: European cross-currents in Manchester chamber concerts, 1895-1929’. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation: Manchester Metropolitan University, 2016, p. 198, 215, 282-84, 289.

[18] See Geoff Thomason, ‘Zer is no French Modern Musik’, Paris-Manchester Exhibition, RNCM, 2020, p. 4.

[19] See for example programmes of 6 February 1912 and Northwich, ‘Coming of Age Celebration’, 3 February 1914, Concert Programmes, RMCM E/1/4.

[20] See on 21 November 1911, 3 July 1913 and the Preston ‘Coming of Age’ concert, 18 February 1914. RMCM E/1/4.

[21] Annual Report of Council, 1915, p. 12; 1916, pp. 11-12; 1917, p.12; 1918, p. 12; 1919, p. 11, RMCM/B/3/3.

[22] Geoff Thomason: ‘Brodsky and his circle’, pp. 3, 23, 66, 77-85.

[23] See Thomason, ‘Zer is no modern French Musik’, p. 10-11.

[24] See Sonata for Violin and Piano, Brodsky Quartet concert on 4 December 1919 with Franck Merrick. RMCM E/1/5.

[25] See Ali Ronan, See Ali Ronan, ‘…we are utterly odd. A collaborative life in both music and politics: A brief analysis of a series of wartime letters written between 1917-1919 between the composer and singer, Hope Squire Merrick (1878-1936) and her imprisoned husband, the pianist and conscientious objector, Frank Merrick (1886–1981). Paper given at the Paris-Manchester conference, ‘Les Institutions musicales à Paris et à Manchester pendant la première guerre mondiale’, 5-6 March 2018, Conservatoire nationale supérieur de musique et de danse de Paris.

[26] See programme from 9-16 March 1917, RMCM/E/1/5. The song was performed again at the Opéra-Comique concert of the Paris-Manchester project and again at the RNCM by Paris Conservatoire students.

[27] Geoff Thomason, ‘Brodsky and his Circle’, pp. 3-4, 22, 42, 44, 46, 141, 163, 171, 188, 224, 238, 303, 308.

[28] For a discussion about Wagner in France during the First World War see Marion Schmid, À bas Wagner! The French Press Campaign against Wagner during World War I’ in ed. Barbara L. Kelly, French Music, Culture, and National Identity, 1870-1939 (Rochester: Rochester University Press, 2008), pp. 77-91. See also Rachel Moore, Performing Propaganda, Musical Life and Culture in Paris During the First World War (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2018), pp. 11, 15, 64, 65-8, 71, 72-96, 218.

[29] Fuchs met a Russian nobleman and composer Mensenkampff and asked him to write a work for him. Petite Suite for Violin and Piano was subsequently performed at the RMCM in May 1915.

[30] See Geoff Thomason’s detailed account of Brodsky’s and Fuchs’ detainment, ‘Brodsky and his circle’, chapter 7, ‘A Tale of two citizens’, pp. 204-39.

[31] See Ali Ronan, ‘…we are utterly odd. A collaborative life in both music and politics: A brief analysis of a series of wartime letters written between 1917-1919 between the composer and singer, Hope Squire Merrick (1878-1936) and her imprisoned husband, the pianist and conscientious objector, Frank Merrick (1886–1981). Paper given at the Paris-Manchester conference, ‘Les Institutions musicales à Paris et à Manchester pendant la première guerre mondiale’, 5-6 March 2018, Conservatoire nationale supérieur de musique et de danse de Paris.

[32] See also Herbert Taylor and Sydney Wilson who died on active service.

[33] Obituary, ‘Lieut. F. B. Tipping (killed)’, The Manchester Guardian, 3 September 1917.

[34] RMCM Twenty-Sixth Annual Report of Council, 1919, p. 10.

[35] RMCM Twenty-Seventh Annual Report of Council, 1920, p. 10.

[36] RMCM Twenty-Seventh Annual Report of Council, 1920, p. 11.

[37] See Students’ Open Practice programmes of 30 January 1923 (Brahms, Clarinet Quintet), 27 February 1923 (Brahms Clarinet Quintet and Sonata in F minor and obligato to Schubert song), 13 March 1923 (Mozart Concerto).

[38] ‘Special Report’, RMCM Thirteenth Annual Report of Council, 1923, pp. 10-11. The report expresses some relief that the College has returned to normal.

[39] Annual Report of Council, 1920, p. 11; 1921, p. 11; 1922, p. 10; 1923, p. 13. RMCM/B/3/3.

[40] RMCM Twenty-Third Annual Report of Council, 1916, p. 10.

[41] Barbara L. Kelly, ‘Une entente cordiale en musique: The Chesterian dans l’entre-deux guerres’ in ed. Timothée Picard, La Critique musicale au XXè siècle, (Rennes: Presses universitaires, 2020), pp. 1043-52.