Paris-Manchester 1918

Conservatoires in time of war

Zer is no modern French Musik (Geoff Thomason)

Only a few hundred metres from the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester stands an unprepossessing building in the early Gothic Revival style. Built as a Unitarian Chapel in the 1830s to a design by Charles Barry, architect of the Houses of Parliament, since the 1920s it has been a Welsh Chapel, a Kingdom Hall of Jehovah’s Witnesses and a mosque, and has recently been restored as student accommodation.

To architectural historians, the building is important as England’s first non-conformist place of worship to be built in the Gothic Revival style. To musicians, it is notable that in 1904 the Unitarian Chapel appointed as its organist one Emile Alfred Debussy, cousin of the rather better-known Claude Achille. Emile’s father Jules had moved to Manchester in the 1870s and settled in the Chorlton on Medlock area, where Emile was born in 1880. Chasing them through various censuses is not helped by the transcribers’ inability to spell their names. The family’s surname is given variously as De Beesey, Bussy and De Bussy and at one point Emile becomes Emily. In the 1901 census Emile is listed as a ‘Teacher of music’ and his father as a ‘Teacher of French, and in 1911 Emile has adopted the title ‘Professor of music’.[1] In reality he was, like his father, teaching the piano and accompanying various choral societies. In December 1880 Jules was one of the pianists in a charity concert in Chorlton [on Medlock] Town Hall; twenty years later Emile appears as an accompanist in concerts given by Manchester Male Voice Chorus.

The presence of Debussy’s relatives working as musicians in Manchester begs the question: what might they have done to promote his music? The simple answer is that they apparently did nothing. Claude Debussy never came to Manchester – and the lack of any surviving correspondence suggests that he was not particularly close to his Mancunian cousins. They were, after all, one of many immigrant families living in Manchester towards the end of the 19th century. As Manchester grew throughout that century from being ‘the largest village in England’ to one of the foremost industrial cities of the British Empire, so its burgeoning population became more cosmopolitan.[2]

By 1900 it was the sixth largest city in Europe and the largest not to be a capital. Within Manchester’s immigrant population, the French remained a small minority. The largest community by 1901 were the Russians and Poles, who had settled in parts of north Manchester and neighbouring Salford. To the north-east, many Italian mill-workers lived in Ancoats, while just south of the centre, in Chorlton on Medlock, lay Manchester’s ‘Little Ireland’. All of these immigrant communities were overwhelmingly working class, and consequently had little engagement with the city’s musical life. The Ancoats Brotherhood was set up in 1881 to improve the cultural life of one of Manchester’s poorest areas through chamber concerts and lectures, but by the turn of the century the press was remarking how its core audience had become one of ‘champagne socialists’ from the affluent southern suburbs. Music at the Brotherhood largely reflected the tastes of its founder, Charles Rowley, who revered Beethoven.

Although not the largest immigrant group, Manchester’s German community was one of the oldest and, more significantly, mostly middle class, well off and possessed of cultural savoir faire. It was they who had invited Charles Hallé to Manchester in 1848, in which year their numbers were swelled by emigrés from the volatile political situation in Germany. After Hallé’s death in 1895, attempts to replace him with the British Frederic Cowen were thwarted by what the composer and conductor Landon Ronald called Manchester’s ‘German cabal’ and the appointment of Hans Richter in 1899. Wagner’s sometime amanuensis and conductor of the first Ring cycle in 1876, Richter’s repertoire remained staunchly Austro-German. He instilled in his Manchester audiences an appetite for Wagner which the First World War did little to diminish, but his antipathy to new, or non-Germanic repertoire, is summed up in his alleged declaration that ‘Zer is no modern French Musik’.[3]

Manchester’s Germans had their own club, the Schiller-Anstalt, which, until it closed in 1912, operated a regular programme of chamber concerts, often featuring high-profile German musicians. The clarinettist Richard Mühlfeld appeared there, as did, in 1904, Richard Strauss. A cumulative repertoire list published in 1902 shows Beethoven to have been the most performed composer there, followed closely by Brahms. Chamber music could otherwise be heard at the concerts given by the Brodsky Quartet. Brodsky had succeeded Hallé as Principal of the Royal Manchester College of Music (hereafter RMCM) in 1895, only two years after its founding by Hallé himself. Although Russian, Brodsky’s training and earlier career had been spent largely in Vienna and Leipzig, and his programmes, too, reflected his preference for a conservative, Austro-German repertoire, with Beethoven at its core. It is no accident that the Quartet chose to make its debut at the Schiller-Anstalt in 1896.[4]

All in all, this was not an environment in which French music was likely to flourish. Yet by 1918, the year of Debussy’s death, French music, not least by Debussy himself, had carved a sizeable niche in Manchester’s musical landscape. It is tempting to regard this as the outcome of a turning against German music during the First World War, but that would be too simplistic. In contrast with the situation in Paris, there was no widespread rejection of German music in Manchester during the war. The dichotomy whereby German music continued to be valued and played against a backdrop of growing anti-German sentiment remained unresolved. The Brodsky Quartet continued to offer the patrons of the Ancoats Brotherhood Beethoven and Schubert while its guest speakers indulged in polemics against German culture.

The cause of French music was urged as often as not as much by individuals as by institutions. The pianist Frank Merrick (1886-1981) was appointed to the staff of the RMCM in 1911, but prior to that he had been including music by Debussy in his recitals since at least 1907. Several of the Préludes feature in his programmes together with the piano Images and the suite Children’s Corner. A recital from July 1907, in which he played ‘Reflets dans l’eau’, Images (first series, 1905) and ‘Jardins sous la pluie’, Images (second series, 1907) contained the following information for the audience:

Debussy (who is a Frenchman) is the latest of new and strange things in music. He may be said to have invented a musical diction of his own, which is at least most interesting.[5]

Merrick and his wife, the pianist and composer, Hope Squire (1878-1935) gave two-piano recitals in which new pieces were presented anonymously to encourage the audience to receive them with an open mind. At one such recital, in November 1915, they performed a duet version of La Mer, and a year later Merrick gave a lecture in Manchester on ‘The value of Debussy’s works to the pianoforte teacher’.[6]

Imprisoned during the latter years of the war as a Conscientious Objector, Merrick was a natural outsider, unafraid to challenge social norms. Equally maverick was the conductor Thomas Beecham (1879-1961), who was blessed with the ability to épater le bourgeoisie while charming them in the process. After Richter’s retirement in 1911 he had been replaced at the Hallé by the German Michael Balling. Balling’s tenure ended prematurely with the outbreak of war, and Beecham stepped in as one of several temporary conductors during the war years. Now the Hallé had a conductor who not only championed French – and Russian – music, but for whom the status of France and Russia as allies gave him carte blanche to indulge his preferences. In his first season he gave Manchester its first taste of Stravinsky’s Petrushka and Firebird alongside new British music by, among others, Bax and Delius.

The press was not slow to notice:

The war has had an extraordinary effect on the Hallé concerts, and the season has had a greater musical interest and produced a wider variety of programs [sic] than any for years gone by. The unique conditions have never caused any despair, but rather a keener courage and a bolder outlook…[7]

By the end of the season Beecham had programmed Debussy’s Nocturnes – with Stravinsky’s Japanese lyrics. The concert produced a mixed critical response.

The three Nocturnes by Debussy came too late in the evening to be appreciated… By this time our ears were accustomed to daring progressions, but they were unprepared for the assault made on them by Stravinsky’s Japanese songs… [8]

Nevertheless, Beecham repeated the Debussy at a concert the following December, which also included L’Apprenti sorcier by Dukas.

Press announcements of the Hallé’s 1915-16 season promised more French music. As well as repeating the Nocturnes, Beecham programmed Debussy’s Petite suite alongside Franck’s Les Djinns in February 1916 and shortly afterwards tapped into Manchester’s growing sympathy with Franco-Belgian nationalism with Bizet’s La Patrie. He even performed Fêtes from the Nocturnes at the otherwise conservative Gentlemen’s Concerts.[9] The pianist Robert Forbes (1879-1958) played Ravel’s Valse nobles at a Beecham concert ‘consisting almost entirely of music new to Manchester audiences’, which also included D’Indy’s Symphony on a mountain air.[10] In January 1916 Beecham conducted Franck’s Le chasseur maudit.[11]

1917 brought the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune – not for the first time, as one press review noted that:

The exotic nature of Debussy’s Prélude is enhanced at each successive hearing…[12]

Beecham was wise enough to continue to offer Wagner, both in his Hallé concerts and in the visits by his own Beecham Opera Company. One critic noted the apparent anomaly after one of Beecham’s Wagner nights in January 1917.

The amiability of the English character was shown in the reception accorded to music of an alien source, for both Russia and Italy, and, we believe, France have enacted that music of German origin shall no longer be performed during the war…[13]

By now other conductors were offering Manchester’s audiences the chance to experience the unfamiliar. A notable precedent had occurred in 1911, when Henry Wood chose Manchester to première the orchestral version of Ravel’s Pavane pour une infante défunte.[14] In February 1916 the Polish conductor Emil Mylnawski gave Ravel’s Ma mere l’oye, but:

Ravel’s delicious ‘Mother Goose’ suite did not receive the applause it deserved – it is a maze of sound and colours, but there is nothing unnatural in expression or harsh in effect.[15]

Eugene Goossens paired Ravel’s Rapsodie espagnole with Tchaikovsky’s ‘Polish’ symphony in November 1916 and, deputising for an indisposed Beecham, conducted Debussy’s La demoiselle élue in February 1917. The anonymous critic of the Manchester City News recorded that the solos were sung in French, with the choral parts being in English.[16]

French repertoire was also beginning to feature in the city’s other concert series. Ironically, Debussy’s String Quartet was first heard in Manchester at the Schiller-Anstalt, played by the visiting Brussels Quartet in 1907, but one of the first home-grown quartets to take it up was that led by Arthur Catterall (1883-1843). One of Brodsky’s most gifted pupils, Catterall represented the generation of RMCM students which had come of age on the eve of the Great War and were now forging their own professional careers.

Ever ambitious, Catterall established his own chamber concerts, but in the war years and after he and his young contemporaries frequently appeared at the new Tuesday Mid-day Concerts, founded in 1915 as an offshoot of the Manchester branch of the Committee for Music in Wartime. It was here, most of all, that French music found its natural home.

There are a number of reasons for this, beyond a wish to mirror the promotion of the music of the allies elsewhere. One is that a lunchtime concert lasting barely an hour offered reduced scope for extended works, but was ideally suited to the vocal items and shorter instrumental items. Lucy Pierce, a former RMCM student and by 1916 one of its teachers, gave the first Manchester performance of the Ravel Sonatine in June that year, leading the Manchester Guardian’s critic to comment that it:

…showed the melodic aspects of the composer’s style in a more than usual predominance… The continuity of the melodic style throughout the work is carried almost to dangerous lengths, but the piece has more warmth of expression than is found in the composer’s more technical pieces, and Miss Pierce’s musical interpretation would do much to recommend this as yet insufficiently appreciated pianoforte composer to her hearers…[17]

Music by Debussy is especially prominent. Throughout the war and after audiences at the Mid-day Concerts were offered the opportunity to hear a number of his songs and piano pieces. Frederick Dawson had included Clair de lune in the very first piano recital the series, on 23 November 1915, and played Reflets dans l’eau and the Toccata from Pour le piano in his return recital the following January. Piano or vocal music by Debussy featured in no less than eight concerts during 1916 alone. The following is a selection:

Figure 1: Selected Debussy performances in Manchester in 1916

– ‘Clair de lune’, Suite Bergamasque and the G major Arabesque (W. Scott, 15 February)

– 2 movements from Children’s corner (Edward Isaacs, 7 March)

– ‘Yver vous n’estes qu’un villain’, Trois Chanson de Charles d’Orléans, Manchester Vocal Society, 21 March, in English)

– ‘Bruyères’ and ‘Minstrels’, Préludes (Books 2 and 1) (Lucy Pierce, 11 April)

– ‘Danse de Puck’, Préludes (Book 1) (Leslie Heward, 2 May)

– 2 movements from Children’s corner (John Wills, 4 July) [18]

There was also a performance of La Demoiselle élue in September 1917 – its second in Manchester that year. The previous January the Philharmonic Quartet had also played the Debussy String Quartet at the Gentlemen’s Concerts.

Moreover, many of the performers at the Mid-day concerts were women. This reflected, not only the lack of men during wartime, but also the fact that the predominance of vocal and piano music was able to showcase two areas that had traditionally been acceptable for female musicians. Before the war, the majority of RMCM students had been young women, almost entirely pianists, singers or violinists. Many of their generation were now turning away from the heavily Austro-German repertoire of their teachers and exploring newer, less familiar music. In this respect the move towards French repertoire in the Mid-day concerts is paralleled by a greater role for English music, not least the school of English songwriters coming to the fore in the early twentieth century.

French music had even begun to filter down to the concerts given by Manchester’s numerous amateur music societies, which during the war were valued as much as a badge of civic pride as a means of boosting morale. One reads, for instance, of Sydney Seal playing Children’s Corner in a concert by Ancoats Girls Choir in November 1916. One of the most remarkable amateur bodies was the Manchester School of Music, which offered private tuition for much of the 20th century in the neo-gothic St Andrew’s Chambers opposite Manchester’s Town Hall. Its Director Albert J. Cross (1872-1925) was a passionate enthusiast for new music and responsible for giving numerous pieces their Manchester premières. One of the teachers at the School, James Richardson, is particularly significant as the first British ‘cellist to champion Debussy’s Cello Sonata.

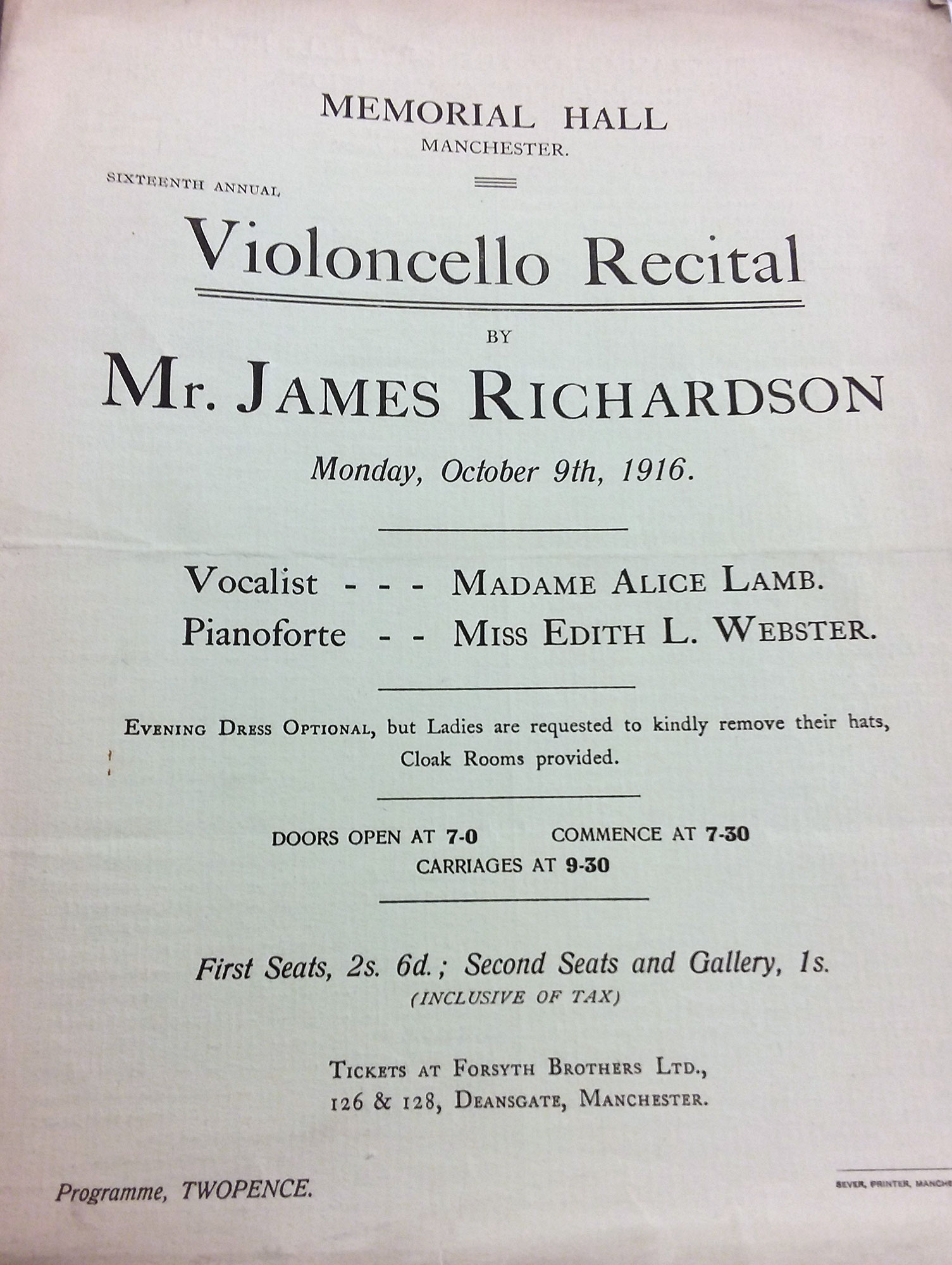

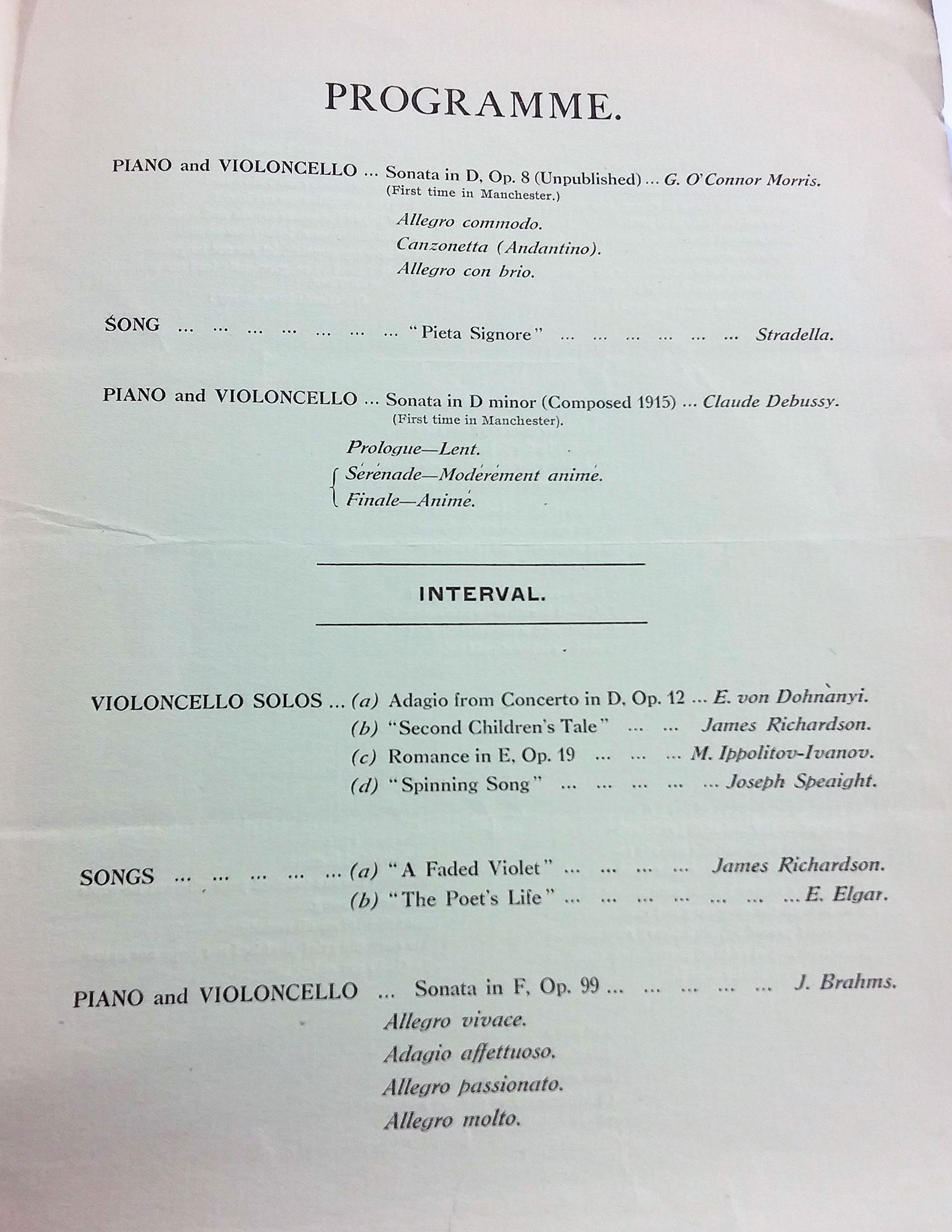

What we know of Richardson is that he was born c.1872 and is described in the 1901 census as ‘Professor of Music’ and in 1911 as ‘Musician Violoncellist’. 1899 he had been elected to the Incorporated Society of Musicians and by the outbreak of war he was living in the suburb of Moss Side and advertising himself as a ‘cello teacher. He also gave an annual recital, with an emphasis on promoting new repertoire. On 9 October 1916, with the pianist Edith Webster, he included the Debussy Cello Sonata, which had only been completed the previous year. There was a brief review in the Manchester Evening News, which simply mentioned that ‘[a]n excellent performance was given’.[19] The Manchester City News was barely more fulsome, noting that it was ‘a rendering reflecting credit on both Miss Webster and the concert-giver’. [20]

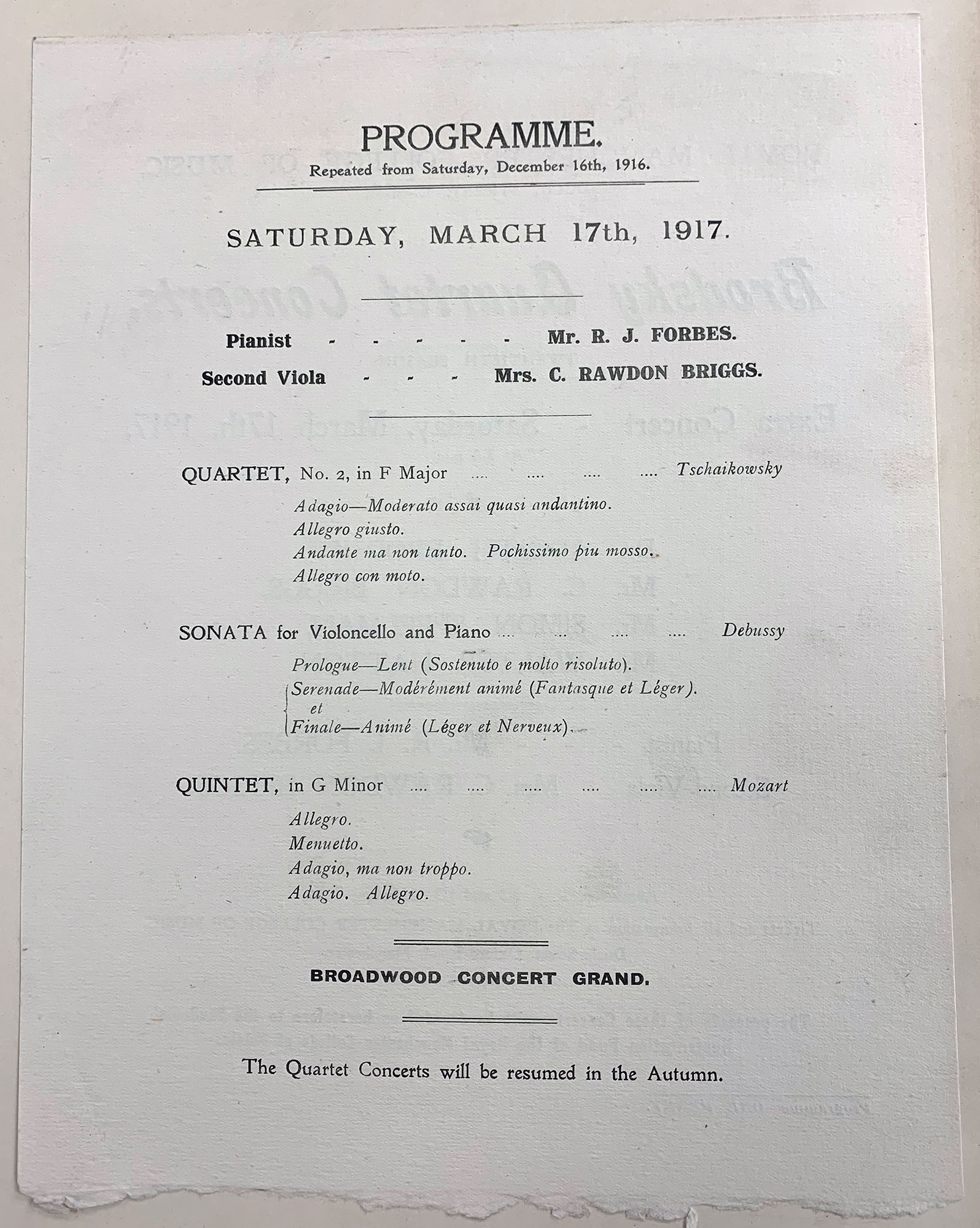

Richardson’s performance was not quite the crown of the year in which Manchester appears to have discovered Debussy. Barely two months later, the Cello Sonata received a second performance, this time by Walter Hatton and Robert Forbes, and moreover in one of the Brodsky Quartet Concerts, not otherwise known for being innovative [See Figure 2]. Hatton was at this stage the quartet’s cellist. This time the Manchester City News critic took more notice, and appeared to be more informed as to Debussy’s latest compositions, not least his intention of completing Six sonates pour divers instruments, pointing out:

…the wistful phrases in each of the three movements [were] emphasised as noticeably as their lyrical beauties and rigorous fancifulness. The piece as a whole was thereby made to appear less characteristic of Debussy than are several of the series of six… It is questionable whether the influence of the lament in the opening movement is intended to pervade the remainder so solidly as in Mr. Hatton’s sombre phrasing…[21]

Owing to bad winter weather, the audience was small and the concert was repeated the following March, but by then there had been yet another performance of the sonata, this time by Johan Hock, the ‘cellist of the Catterall Quartet and again with Robert Forbes. This time the City News critic is named as Thomas Moult, otherwise one of the city’s many church organists.

Figure 2: Debussy’s Sonata for Violoncello and Piano, Brodsky Quartet Concert, 17 March, 1917

…There is more than painting in Debussy’s new sonata. The suggestions of abstraction and spiritual aestheticism in the daring opening are bound up with a logic of conception unfathomable in the conventional musical audience… because it is absolutely apart from the logic dictated by the subject. Mr. Forbes at the piano did his best to make tangible what is, in the light of understanding of Debussy’s music, altogether intangible; and though Mr. Hock was certainly handicapped by the solidity of the pianoforte, his ‘cello playing showed sufficient of the piece to give hope that his next rendering, helped by more congenial atmosphere, will assist to a fairer judgement of the sonata…[22]

Moult got his chance to review the sonata again when Hatton and Forbes gave their second performance.

…the Sonata for Violoncello and Piano by Debussy, in which the ‘cello was again revealed as an instrument strongly akin to the Debussy spirit. Full of strange and flowing emotions with which the composer has already dealt more fully elsewhere, the piece was like a spiritual arousal after travail. Mr. Hatton and Mr. R.J. Forbes made a very vivid thing of its jocular tauntings no less than its bizarre pleading…[23]

A year later Debussy was dead. From his prison cell, Frank Merrick wrote to his wife:

And so Debussy is dead – and…he has not left such stacks of works behind him; how much poorer the present seems without the immediate prospect we so lately enjoyed of seeing exquisite creations drop off the point his pen… [24]

If Debussy’s standing in Manchester in the final year of the war was higher than it had been at the outset, it was thanks in part to the advocacy of individuals like Merrick. Although Manchester’s appetite for German music was strong enough to survive the war, we can point to a number of factors which accelerated the absorption of newer French repertoire. A change of direction at the Hallé, with Beecham the right man in the right place at the right time. The development of the lunchtime concert as a new model for performance. The impact of a younger generation of local musicians keen to explore new repertoire. The increased number of opportunities for women as performers and the work of innovative pioneers like Merrick and Richardson. One wonders what Emile Alfred Debussy made of it all.

Geoff Thomason, RNCM, 2018

[1] The 1911 census return transcribes this as Proffessor [sic] of music.

[2] The term ‘largest village in England’ alludes to Manchester’s lack of parliamentary representation between 1660 and 1832. It regained the right to elect MPs under the 1832 Reform Act, was incorporated in 1838 and granted city status in 1853.

[3] See for example Christopher Fifield, Hans Richter (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2016, revised edition), p. 253.

[4] The ‘cellist of the Brodsky Quartet, Carl Fuchs, also organised the concerts at the Schiller-Anstalt.

[5] Programme for a recital given by Frank Merrick and the ‘cellist Mabel Wilson-Ewer, Clifton, Bristol, 5 February 1907. University of Bristol Special Collections, DM2103/F.

[6] Given as part of Dr [Walter] Carroll’s Lecture Course for Music Teachers at the Onward Hall, Deansgate Manchester, on 30 November 1916. Bristol University: Papers of Frank Merrick and Hope Squire, DM2013.

[7] Manchester City News: 27 February 1915, p.9, referencing the Hallé concert that had taken place two days previously.

[8] Manchester City News: 27 March 1915, p.6.

[9] Founded in the 1770s, the Gentlemen’s Concerts were Manchester’s oldest concert series. By the early 19th century they catered for a well to do, subscription-based audience. Hallé had initially been invited to Manchester in 1848 to conduct the Gentlemen’s Concerts and, with the creation of his own orchestra in 1858, the two co-existed until the Gentlemen’s Concerts, increasingly plagued by financial difficulties, came to an end in 1920. C.f.: Wilfred Allis. The Gentlemen’s Concerts: Manchester 1777-1920. M.Phil. dissertation: University of Manchester, 1995 and Geoff Thomason: Brodsky and his circle: European cross-currents in Manchester chamber concerts, 1895-1929. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation: Manchester Metropolitan University, 2016.

[10] Manchester City News: 14 March 1916, p.8.

[11] Manchester Guardian: 28 January 1916, p.4.

[12] Manchester City News: 3 March 1917, p.2.

[13] Manchester City News: 6 January 1917, p.6.

[14] 27 February 1911.

[15] Manchester City News: 26 February 1916, p.7.

[16] Manchester City News: 17 February 1917, p.8. Goossens (1893-1962) was to act increasingly a Beecham’s unofficial deputy. A keen champion of new music, he conducted the first British performance of The Rite of spring in 1921.

[17] Samuel Langford. ‘Tuesday Midday Concerts’. Manchester Guardian: 14 June 1916, p.10.

[18] Programmes held at Manchester Central Library Re780.68It22.

[19] Manchester Evening News: 10 October 1916, p.1.

[20] Manchester City News: 21 October 1916, p.7.

[21] Manchester City News: 23 December 1916, p.3.

[22] Manchester City News: 17 February 1917, p.8.

[23] Manchester City News: 17 March 1917, p.8.

[24] Frank Merrick to Hope Squire: 18 April 1918. University of Bristol Special Collections, DM2103/F/5/2.