Bury Me Deep

31 March 2024

Introduction

This is the second of four blog posts in which Dr Sam Salem (RNCM PRiSM Senior Lecturer in Composition) discusses his recent works for performers, electronics and fixed audiovisual media: THIS IS FINE (2021), Bury Me Deep (2022), Shadows pass the morning ‘gins to break (2022), and The Way Up & The Way Down (2023).

In this blog, Salem continues to reflect on his earlier engagement with Neural Synthesis, incorporating PRiSM SampleRNN to create an AI doppelgänger of trombonist Weston Olencki, while exploring the aesthetics of the post-industrial, psychogeography, and an elusive “crisis of consciousness”.

Bury Me Deep (2022)

By Sam Salem

Bury Me Deep is a work for solo trombone, live electronics and fixed audiovisual media, composed for and with Berlin-based American trombonist Weston Olencki (they / them) between 2018 and 2022. It builds upon my auto-ethnographic and psychogeographic work Midlands, and The Raft Breaks, my solo violin work written for Linda Jankowska.

This blog post aims to elucidate my thinking in and around the piece. Bury Me Deep was a challenge to compose as I knew, from my initial conversations with Weston (in the summer of 2016), that this would be the last solo work that they would commission, as they moved away from performing the work of other composers to focus on their own compositions. It was also a challenge as the compositional process fell into the black hole of the pandemic.

The focus of my research was Weston Olencki themself: their beginnings, their talents, their energies. It is therefore appropriate that we begin our story as I began the project itself, with a journey to a small town in the deep south of the United States.

I Wanted To Live Free But I Died Too Poor (Kiss It)

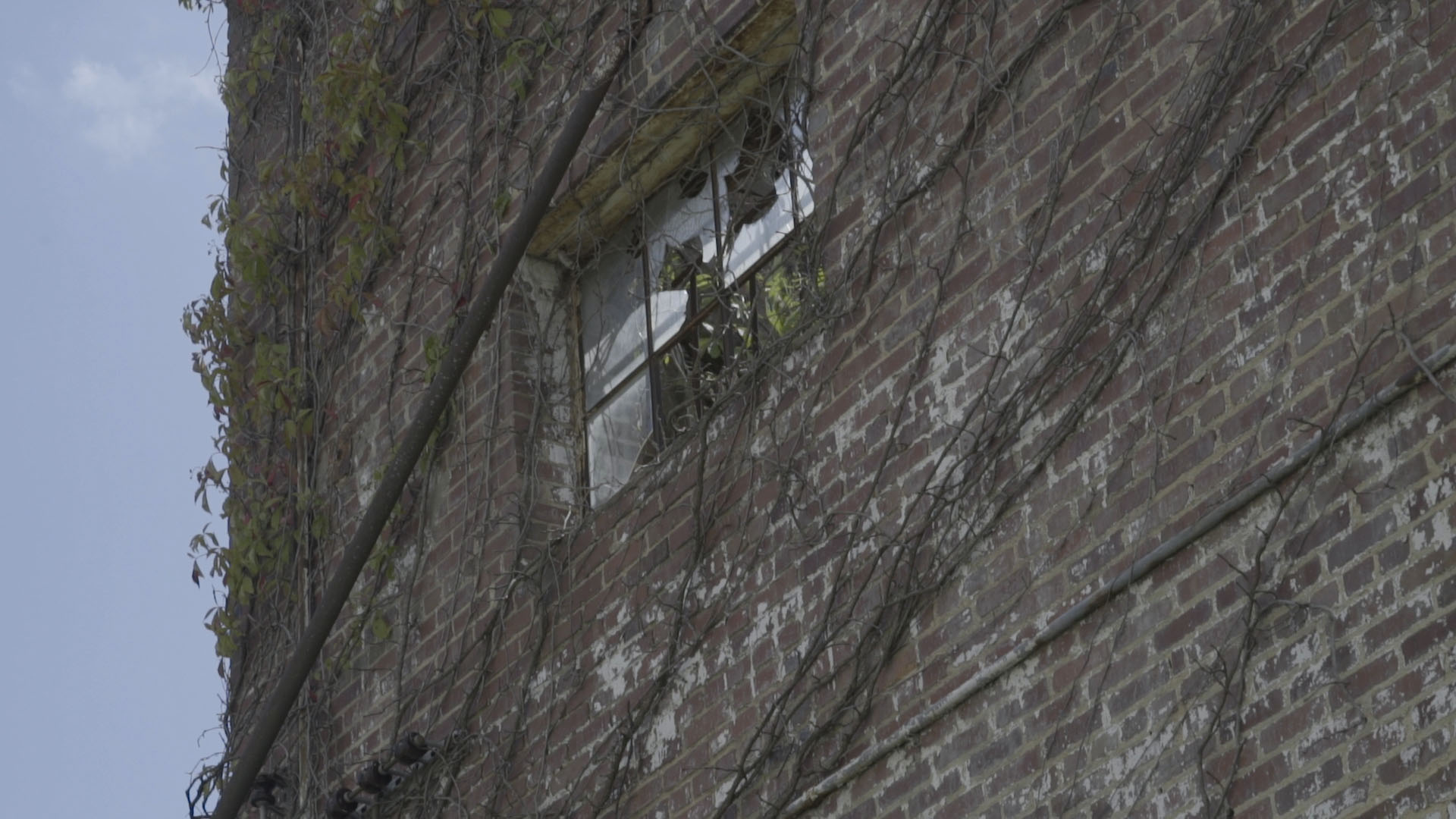

In 2018 I travelled to Spartanburg, South Carolina, Weston’s childhood hometown.

As a composer, I am heavily indebted to and inspired by psychogeography – my works draw from the architectures, histories and myths of my chosen locations. It is therefore a strange coincidence that Weston’s hometown should share so much dark history with Derby, the town where I grew up. During the Industrial Revolution, the exponential demand for cotton created in one location was fed by slavery and suffering in the other – this cannot and should not be ignored, but is also not at the centre of this work.

As an outsider (in both Spartanburg and Derby), I felt that I should not try to approach this history directly. Nevertheless, exploring Spartanburg with Weston, I felt the presence of this shadow in every empty lot and former mill, and at the site of every battle.

We traversed the town, following our intuition. We crisscrossed the state. To say that summer in South Carolina is stifling is an understatement of epic proportions.

We felt the air, the heat, the moisture, pushing our bodies to hallucination, rendering us superstitious, the creep of gothic horror around every corner. I felt Weston’s complex relationship with this small, pleasant town, and understood it: we share the need to escape, at maximum velocity, from our points of origin.

This atmosphere of extreme and inescapable humidity, the feeling of intense pressure, is my sense memory of Spartanburg. It is this feeling which I attempted to invoke in Movement 1 of Bury Me Deep, through the use of various layers of noise-like texture.

It is otherwise hard to communicate the sites (and sights). We saw abandoned lots, a lot of Freemasons lodges, even more churches of every denomination, crammed into every conceivable (and inconceivable) space. Kudzu on telegraph polls, kudzu on mills, kudzu on street-lamps, kudzu on kudzu.

We heard the electric crackle of cicadas in the summer, the cent-perfect close-harmonies of unnervingly high-quality karaoke. The percussive impacts of football practice, bodies crashing against bodies, the performative solemnity of contact sports – were as seemingly eternal, and of the land, as the flows of the local rivers.

From the beginning, I had envisaged Bury Me Deep as a kind of séance, a conversation between a living trombonist and a “dead” trombone (provided in this instance by Robert, Weston’s high-school trombone repairman, in exchange for a bottle of bourbon).

The hanging, “dead” trombone would serve to embody the acousmatic, disembodied, electronic sound-world of the piece and invisible cloud-based processes: a voice from beyond the boundaries of the stage, granted physical presence through a (literally and figuratively) resonating object.

The “dead” trombone resonated via a transducer attached to its mouthpiece, and is amplified by two contact microphones attached to its extremities. Receiving a combination of fixed media and live electronics, it sounds as follows:

The invocation of Spiritualism is intentional, and the irrational, occult and Romantic beliefs of which it is indicative, are of concern in many of my works. I have a long-standing fascination with what James Webb described as the “Age of the Irrational” in his 1971 book ‘The Flight From Reason’:

Western man as a whole was undergoing a severe trial of his capacity to adapt to an environment which for the first time seemed beyond his powers to order… As man advanced to greater mastery of the physical, so his always precarious hold began to slip upon the more intangible aspects of his relationship with the universe. His society, his awareness, his methods of thought, and most importantly the conclusions he reached, were all changing round him. What is more, they could be seen to be changing: and this was frightening…

…Spiritualism is at once the most primitive and the most comprehensible of responses to the crises of consciousness. As the tide of rationalism and the new science rose higher; as the sense of collective insecurity waxed, men turned to the immortality of souls. They could shout in the face of the bogey Darwin that they knew they were more more than the outcome of a biological process, that they too had ‘scientific proof’ – and that theirs was of the reality of the after-life.

Did this “crisis of consciousness” ever end? Perhaps a more interesting question – did it ever truly begin?

The medium, the necromancer who talks to the dead, offers us the chance to suspend our disbelief. If the hanging trombone provides a mouth, then we should next discuss the ghostly voice itself.

Without Signs of Tiring

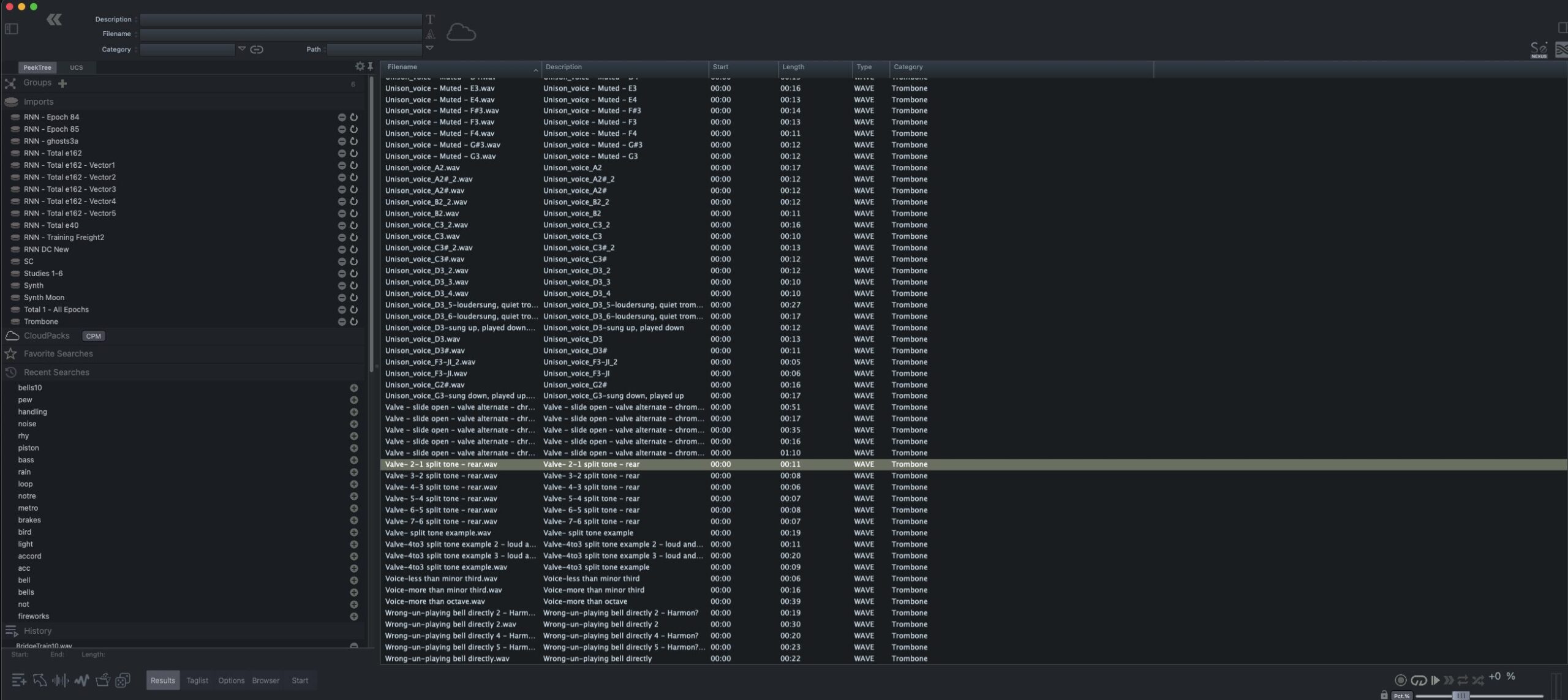

I invited Weston to the RNCM in December 2019 in order to create another crucial set of materials for this piece. We spent a week exploring Weston’s relationship with their instrument, creating a database of over 3,500 individual recordings. These recordings, which took several months to edit and catalogue, form a comprehensive snapshot of Weston’s approach to their instrument, covering standard, extended, and highly idiosyncratic techniques.

My intention was to use this database as a dataset for a series of PRiSM SampleRNN models (as described in my earlier blog post, The Psychogeography of Latent Space).

We aimed to create an AI doppelgänger of Weston, a breathless, uncanny cipher, that would “play” the hanging trombone – an instrument without a body, “played” without understanding, ceaselessly and without signs of tiring.

While this technology has lost a little of its novelty since 2019, it is important to emphasise that Neural Synthesis (and the use of ML to generate sound) was still in its infancy at this time.

These tools were employed in Bury Me Deep for both conceptual and material reasons. The former, to link the history of the Industrial Revolution with the post-industrial – and the (perhaps) inevitable slide towards post-work, the latter due to the unreliable, surrealist, uncanny and oracular nature of early Neural Synthesis algorithms. Here is an (isolated) excerpt of the PRiSM SampleRNN material, taken from the first movement of the piece.

The third set of materials (after the field-recordings made in South Carolina, and the spooky output of pseudo-Weston) was created using synthesisers freely re-synthesising fragments of Appalachian music and a recording of Robert (the erstwhile trombone technician) playing his resonator guitar.

From Sunrise to Sunset

These materials form the basis of the final work. In addition to the acoustic trombone (amplified using a condenser and a contact microphone), and the hanging trombone (resonated using a transducer and amplified using a pair of contact microphones), the piece also contains a layer of unusually long delay lines. These fulfil the function of “looping”, but also forms a literal memory, which cuts in and across various layers of material.

The final work moves “From Sunrise” “To Sunset”, from the present to the past, from fragments of South Carolina as it is now, to AI-mediated footage of a Drum Corp competition performance (featuring a young Weston Olencki, dancing tenderly with hundreds of others).

This ghostly choreography, this mesmeric spectacle, is like a dream on a humid summer night. In the end, the ghosts, now speaking to us openly and directly, tell us to live – for us and for them.

Weston Olencki’s Reflection on the Project

“When I marched DCI (Drum Core International) there was this incredible rush you got as you entered the field – always at night under the stadium blaze, the day’s heat still lingering on the worn grass. Before the show there was this pressure, this exhilaration at the beginning of the sprint, one that would be over in a precisely 11-minute example of pure flow state. Each entrance in Mv 2 sets up this same kind of flash, the unspooling of a gorgeous yet impossibly tangled skitter of notes hanging in the mire of that saturated summer air. It’s a sense-memory, one that’s core to myself as a musician, that I really haven’t found replicated elsewhere.

Mv 1 leads us in with these ghosts, not just via the SampleRNN reconstructions, but even the prescribed gestures feel like uncanny doppelgangers of my own idiosyncrasies. These fragmentary half-remembered moments all coalesce without one realizing what’s actually happening, the musical throughlines themselves buried deep. Through the fog you suddenly find yourself at the midst of an overlook, a dense ecosystem that’s always already been there. It’s a vision of the south that I think really cuts to the core of what it is to me. With necessary work and struggle, immersing oneself in the pressure, the malaise, the brackishness, the fecundity, one empties out at the sublime. That this land, left to the sands of time, still holds within its depths these moments of striking, melancholic beauty.”

Sleeping On / The Present

Following the premiere on 30th November 2022 at Iklectik Art Labs, London, Bury Me Deep has received a further 8 performances, at KM28 in Berlin (May 2023), in Huddersfield as part of the Electric Spring Festival (February 2024), and across the East coast of Canada as part of the Sleeping On / The Present Tour In August-September 2023. We drove over 3,000km passing through Montreal, Rimouski, Percé, Fredericton and Halifax, before our last performance at Moncton University on the 9th September 2023.

I am very fortunate to work with collaborators as talented as Weston, who continues to amaze me with their commitment to this work – it’s not something that I take for granted.

Bury Me Deep, alongside The Raft Breaks and The Way Up & The Way Down, will be released by No Hay Discos in summer 2024 as part of my second album.

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by PRiSM, the Centre for Practice & Research in Science & Music at the Royal Northern College of Music, funded by the Research England fund Expanding Excellence in England (E3).

![]()