Norrisette and Not-Norrisette

19 March 2024

Introduction

Anna Appleby (PRiSM Doctoral Researcher 2019-2024) is a Manchester-based composer and songwriter. Her contemporary classical and electroacoustic work has been performed all over the world, while she also makes electronic pop music and performances under her alter-ego Norrisette.

Anna Appleby (PRiSM Doctoral Researcher 2019-2024) is a Manchester-based composer and songwriter. Her contemporary classical and electroacoustic work has been performed all over the world, while she also makes electronic pop music and performances under her alter-ego Norrisette.

Recent premieres include an opera, Drought, for the BBC Philharmonic as part of her doctoral research in collaboration with poet Niall Campbell, and an award-winning collaborative youth opera for Glyndebourne, Pay the Piper.

In this PRiSM Blog, Appleby reflects on her work spanning from Opera to Pop, as well as her creation of Norrisette – an expansion of her voice through technological experimentation and through collaboration with PRiSM SampleRNN, with artificial intelligence.

Norrisette and Not-Norrisette

By Anna Appleby

From Opera to Pop

My collaboration with artificial intelligence came about almost by accident: I was originally focused entirely on composing an opera with poet Niall Campbell for the BBC Philharmonic for my PhD, when the pandemic struck. From this point it was impossible to get an orchestra together, so I eventually started composing and producing for myself at home while awaiting the lifting of restrictions.

Norrisette © Robin Clewley

My past stage fright meant that I felt very reluctant to perform, but I was reminded of a conversation with my colleague Ellen Sargen who had mentioned researching alter-egos in performance contexts. I gradually formulated the idea to create an alter-ego of my own: Norrisette.

Under this moniker, almost anything felt possible, and I embarked on a wholly new musical enterprise, which took me in more creative directions than I could have ever predicted. One of those avenues was my decision, encouraged by Professor Emily Howard, to send my entire recorded Norrisette output to software engineer Christopher Melen on which a bespoke artificial intelligence programme – PRiSM SampleRNN – could be trained. I named the eerie results of these experiments ‘Not-Norrisette’ and ended up integrating this work into both my electronic pop music and, ultimately, the opera.

If you asked me in 2019 how I – a full-time composer whose career is founded on the assumption that humans appreciate and pay for things that are made by other humans – felt about artificial intelligence and music, I would have given you a very negative response. I was, and still am, sceptical about the benefits of AI-generated content and am increasingly aware of the risks it poses to communication, verification, ownership, authenticity and trust.

In my opinion, every technological breakthrough brings the possibility of both advancement and regression, and each tool we use for contributing to the public consciousness can also work against it when profit and power are at stake: smartphones or stupid-phones; social or antisocial media; gunpowder for medicine or death… I persuaded myself to find positive uses for this new technology, instead of fearing it, as it is impossible to opt out.

AI has already been integrated into our lives without our consent. In this instance, machine learning is the term that is perhaps less mysterious, as – in my own limited understanding of the science – it refers to software that is trained on a dataset and then creates its own data in response, based on probabilities. Artificial intelligence implies a sentient force and conjures up images of apocalyptic robot-wracked cityscapes. Perhaps we need more optimistic science fiction writers to inspire us to build a future that we do not abhor.

With help from Christopher Melen (then PRiSM Research Software Engineer), I trained PRiSM SampleRNN – a bespoke artificial intelligence software tool developed to learn from and generate music – with a dataset comprising one hour of my music. This included all of my existing Norrisette recordings, and this was the sum total of its knowledge. The training process began with me sending Melen this dataset as WAV files, which he then fed to the software.

Once the training process completed, he sent me several folders consisting of numerous 15-second WAV files. These files were the algorithm’s response – after going through three complete learning cycles – to the sounds and shapes of my original audio files, and therefore included samples that resembled my own voice and my own original music production. It was effectively imitating my music, so I nicknamed it ‘Not-Norrisette’. This was the first collaboration I had ever undertaken with any machine learning software, and it fundamentally shifted the way I viewed my own practice, like holding up a distorted mirror to my work.

I began to select my favourite files from the collection of outputs, choosing ones which seemed most varied or haunting. There was a strange emotive aspect to the files, and a sense of them being alive, because the software had reappropriated my own voice and imbued it with its own distinctive quality, something unique to the way in which it was created and trained. Having chosen my favourite samples, I began to interweave them with new music to create songs that were a kind of collaboration between myself and Not-Norrisette.

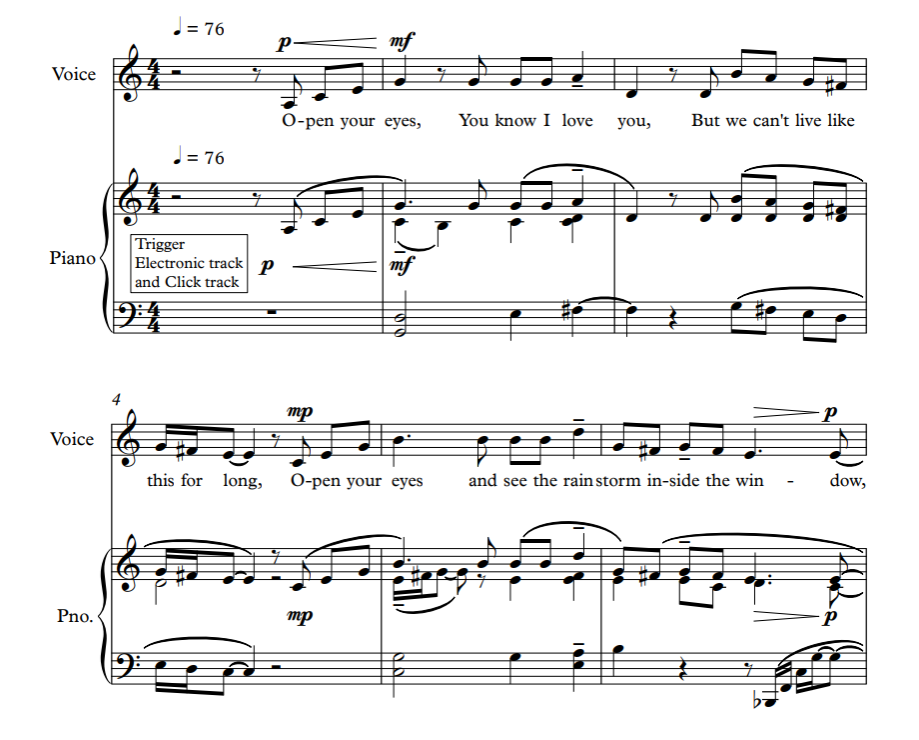

I first composed Reservoir as a song with voice and piano, and then created a duet between PRiSM SampleRNN material and my own voice. I largely left the samples unedited but repeated them when they seemed harmonious in the chorus, for example.

Score excerpt | Reservoir

The title of the track Whale House came from my impression that the PRiSM SampleRNN voice sounded somewhat like a twisted kind of whale song, and I thought it would be a whimsical name for a dance track that involves the typical ‘four-on-the-floor’ kicks of house music.

Originally I added no human vocals, but at the last moment realised that some kind of refrain would elevate the track from being an experimental noise piece to a memorable dance number.

It is now my go-to party piece for live performances, as the obsessive and absurdist question ‘Do you like it in the whale house?’ invites significant audience participation (and slight fear). The music video, like that for Secret Code and Prometheus, has a specific colour scheme, wardrobe and editing style – I use repeated visual motifs in a musical way.

Radio Songs and Broken Radios

Niall Campbell also partially inspired the creation of Norrisette from his initial libretto draft for Drought which involved an otherworldly ‘Rainmaker’ character; I decided that an electronic sound world would be the ideal way in which to expand this character’s voice. Norrisette was incubated by my desire to develop an avant-garde sound world and a more skilled electronic practice in my work.

Cover image: Drought (2022)

One of the original research questions for the opera project was how a composer and a poet might interact without a director’s involvement in the early stages. Working with the BBC Philharmonic, a radio orchestra, created a unique opportunity and challenge to prepare an opera that would be experienced fully by listeners at home without the visual element of staging.

Many choices I made in text-setting and orchestration are to maximise the impact of the story and music through sound alone. I wanted the audience to taste and feel the drought and rain without it being illustrated visually. Campbell’s inclusion of a Radio Song scene in the libretto foregrounds this dimension even further.

In the final libretto draft, the voice that originated as the Rainmaker character has become the voice of the Radio Song.

Norrisette also begins her life in the Radio. The creation of the Radio Song was the moment that I found full permission to integrate my electronic practice with my operatic practice.

To create the ‘broken radio’ or ‘Radio Glitch’ effect for Scene V in the opera, I used material from my collaboration with PRiSM SampleRNN.

Its outputs, a ghost of my own voice and dance beats, were ideal for this scene: the radio, which is previously an object in Scene III that can be switched on and off, is anthropomorphised when Coll says “it hates it here”.

PRiSM SampleRNN seems to have its own particular character and voice, and continues wailing erratically as Coll and Charlie attempt to fix it. I left the ‘Radio Glitch’ track playing into Scene VI so that the radio continues to have a life of its own when the ‘music’ begins again. This juncture is crucial dramatically and musically, as it is the collision of technologies and genres: electronic dance music or hyperpop battles with operatic aria, recorded music and artificial intelligence fight with live voice and orchestra.

That Norrisette and Not-Norrisette became reintegrated into the opera through the inclusion of the Radio Song and Radio Glitch scenes, seemed serendipitous at first, but later I realised that this whole experimental process was a necessary part of me extending my acoustic and orchestral imagination. The resulting orchestration of the opera is doubtlessly more detailed and sophisticated because of my self-initiated training in music production, where every sound matters.

Not-Not-Norrisette

Collaborating with PRiSM SampleRNN enabled me to work more reflexively as Norrisette: realising what sounds were most prominent in my work gave me more self-awareness in both composition and production. Furthermore, the original and haunting sound world that was created by PRiSM SampleRNN, when embedded into my tracks, gave my music a new quality that subsequently led me down more of an avant-garde path. I believe that my later recordings, despite not involving PRiSM SampleRNN, exhibit a more experimental approach. There are sounds and ideas that I am now much more willing to incorporate into my tracks because of the challenging palette that PRiSM SampleRNN presented me with.

I created an EP called Metal Hotel which was centred on experimenting with metallic sounds and with the genre of metal, wholly using electronic music and samples, and not live instruments. This EP was far more avant-garde and sonically adventurous than anything I had made previously, and I believe that my collaboration with PRiSM SampleRNN had influenced the scope of what I thought possible for my music.

I felt confident to make and perform music that was distanced from songwriting and closer to experiments with noise. Crucially, this EP was made immediately after I handed in the complete final orchestration of Drought to the BBC Philharmonic. As a result it represents a new chapter in my musical research, and yet the lyrics of all four songs are immensely tied to the ending of Drought: the horror, regret, fear and isolation experienced by Coll at the end of Campbell’s libretto and my score was palpable in this EP.

I am working on ways to integrate my work as Norrisette with my work as a contemporary classical composer. I create music for electronic technology as Norrisette, and music for the technologies of the orchestra and the classically-trained voice as Anna Appleby.

My work for both are still distinct because of the confines of my performance contexts: work is commissioned from Anna Appleby for specific acoustic performance settings, and work is created by Norrisette to be performed in venues (bars, clubs, music festivals) where using synthesizers, backing tracks, samples and amplified vocals is the current best option as a solo performer and producer who is trained in keyboard and voice.

Alongside moments of electronic and orchestral convergence in Drought, I have been exploring ways to combine genres and technologies in new ways in my work.

Musical technologies interact with genre, as they were developed alongside genres and vice versa. The orchestra and operatic voice were, and are, extended to accommodate the imaginations and demands of composers, while these demands are limited themselves by the constraints of physics, human ability, and the reasonable scope of commercially-operating ensembles.

Likewise recording technology and electronic software have inspired the birth of numerous genres, and are themselves constantly expanded by the aural imaginations of producers. This field is being further developed by experiments with artificial intelligence.

Ultimately, Norrisette became my parallel opera. It is a digital operatic project for contemporary audiences, encapsulating all of the drama that I could embody by myself at home in the pandemic, and has evolved into a living stage work that I re-enact regularly. She is my twenty-first century Gesamtkunstwerk, living digital opera, incorporating artificial intelligence, social media, electronic music, songwriting, fashion, film, photography and digital art.

The three topoi that I initially suggested as fundamental elements of opera in my PhD research (The Voice, Expanded; Sculpture versus Drama; Transformation and Transfiguration) are all present within my work as Norrisette: my voice is expanded through electroacoustic experimentation and collaboration with artificial intelligence; my songwriting holds within it a tension between playing with sound and following some kind of emotional, dramatic form; there is an otherworldly quality to Norrisette which is my drag, my alter-ego, a transformation of myself into something new.

Although I created Norrisette in isolation, the field is now open for future collaborations. She is one of my original contributions to knowledge from this poetic opera collaboration project, as a progressive answer to the question of how to make opera of the future.