Liquid Music

25 September 2023

Alex Mouzouri, by Luca McCarry.

Introduction

During the 2022-23 academic year, PRiSM brought together composition students at the RNCM and researcher-scientists based at the Global Development Institute, University of Manchester.

As part of a Principal Study Elective entitled Collaboration with a Scientist, these composers were brought in direct conversation with scientists working to address global inequalities, climate change, big data, and social and political injustice. Through observing how scientific research is conducted, they created new musical works informed by scientific ideas, curiosity, and methods.

In this PRiSM Blog, RNCM fourth-year undergraduate student Alexander Mouzouri (RNCM School of Composition) reflects upon his collaboration with Dr Timothy Foster (Senior Lecturer in Water-Food Security, Infrastructure and Resilience), and his piece Parallaxenreisen (2023) – a two-movement cycle for mixed ensemble created as a result of this collaboration. Inspired by the complexity, fluidity, and exploitation of water and natural resources across the world, the piece communicates new ways of understanding disruption, reservation, harmony and resonances.

Liquid Music

By Alexander Mouzouri

Introduction

For most of my studies I have been fascinated with the implementation of mathematical principles into my compositional processes.

Before beginning this Collaboration with a Scientist project, I was already thinking about how music occupies time and space; my methods are often driven by complexity and layering. This approach encourages me to spend a lot of time considering ‘tonality’ and ‘familiarity’.

Recently this obsession with ‘tonality’ has channelled itself into two main focuses that drive my music. The first is material with a vague tonal centre (e.g. a chord, a scale/mode) that appears by ‘chance’. Something akin to tonality emerges after a constant distillation and permutation of natural harmonic resonances with artificially constructed modes. This distillation through semi planned harmonic journeys gives a vague direction to the material. The aim of this is to create something of a perpetual musical stew, in which a proverbial Rorschach test of harmonies and semi familiar melodies become apparent through the sheer relentlessness of material transformations.

The second, on the other hand, is complex music that is derived from material that is intrinsically ‘tonal’. In this practice, the result is to hopefully retain some sense of familiarity, the root of the piece being a nostalgic but hidden away spine between shifting layers.

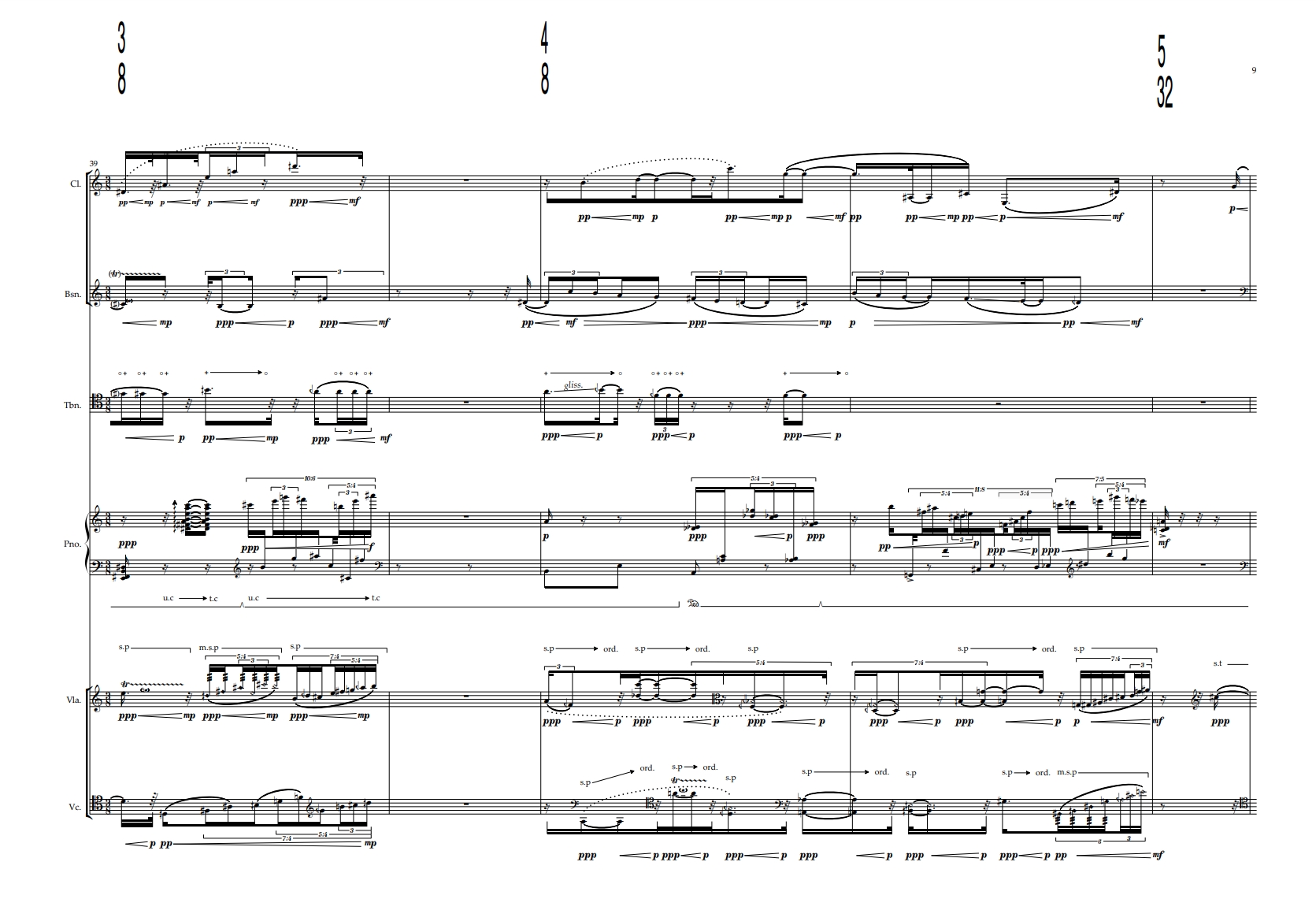

Score excerpt of Parallaxenreisen (2023): First movement – Xanthosis

The question of the necessity of complex notation (that the scores of my music often incorporate) is one I often get asked. When a somewhat similar result can be made through different types of less complex notation, it is interesting to observe how people and players choose to interpret music of this difficulty, and to consider how their processes of negotiating a complexity as such can be positioned at the heart of the music.

My response to this is to raise another counter-argument: what becomes of vaguer notation in years to come. A feathered beam will always be easier to play than a quintuplet inside a nonuplet, but a feathered beam can be played in a thousand different ways. More precise notation on the other hand, will also be played in a thousand different ways (in practice) due to its complexity, however there is an accurate way to play it. This yearning toward a certain goal, I think, provides a piece with a particular quality I have always been fascinated with.

I do think that certainty gives music timelessness, direction and aesthetic beauty.

Liquid Music

In this project I worked with Dr Timothy Foster. Originally an engineering graduate from the University of Manchester, Tim’s work now focuses on water infrastructure in aggregation. His work is generally divided by the Atlantic, with one half being in the dry American southern states and the other being focused on developing countries such as India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

Collaboration with a Scientist: Project meeting with Dr Timothy Foster (middle) and Dr Zakiya Leeming (left).

In the US, a lot of Tim’s work is located around the High Plains (or Ogallala) groundwater system in the middle of the country. In these towns, irrigated farming is the heart of their communities. Not just a way to stay afloat, but a genuine culture and aspect of people’s lives there. That being said, there are some serious problems with over-use and long-term depletion of the groundwater aquifers. This is in stark contrast to what he has observed through working in the East, where the water is plentiful but poor infrastructure and underfunding greatly affect the ability to efficiently extract these natural resources for the benefits of communities local and beyond.

Flying over southwest Kansas, one will see what is left of the country’s so-called ‘breadbasket’. A now parched desert wasteland, the once fertile plains have succumbed to one of the worst droughts in the last 1000 years. Where these thousands of wells once buzzed day and night, extracting a seemingly endless supply of water; many now trudge up only sand.

It is no secret that climate change has much to do with this slow decline of reserves. These farmers and their families are understandably wary to make any changes to their way of life, but the recent shortfalls and dry seasons have sparked some change. For instance, last year, farmers in the region of southwest Kansas met up to discuss possible solutions, with the general consensus being that less water had to be used in their irrigation. 10% less to be exact.

Many of these communities were adamant that they didn’t want any ‘big-city-yuppie-activists’ coming and tampering with their machines. Therefore, a lot of Tim’s work revolves around convincing the farmers that this is for the better. There are lots of double talk to avoid phrases like ‘global warming’ and ‘climate change’, instead opting for words the farmers find more agreeable such as ‘drought’ or ‘dry seasons’.

Having been to these dry southern states recently myself, it is easy to see how these issues have become so stigmatised and over political. Tim works to ensure a decrease in the amount of water used, whilst still maintaining relationships and assurances with the local farmers. This includes deploying specialised devices that are able to total the amount of water being used via a propeller in the pipe, that counts the number of rotations.

Often Tim finds the farmers using clever means to trick the water sensor readings, in order to make it seem like less water is being used. One of the most interesting examples being a man who jammed the sensor with a frozen fish when he heard that the inspectors were coming, clearly trying to make out like the fish had somehow swum in and got stuck, skewing the readings. Unfortunately for him the fish had not thawed out in time.

In my interpretation of Tim’s research, I wanted to split the music into two distinct movements, connected by a common denominator. The first movement represents the mechanical drainage of the North American irrigation system, whilst the second being a more organic cross section through water in motion.

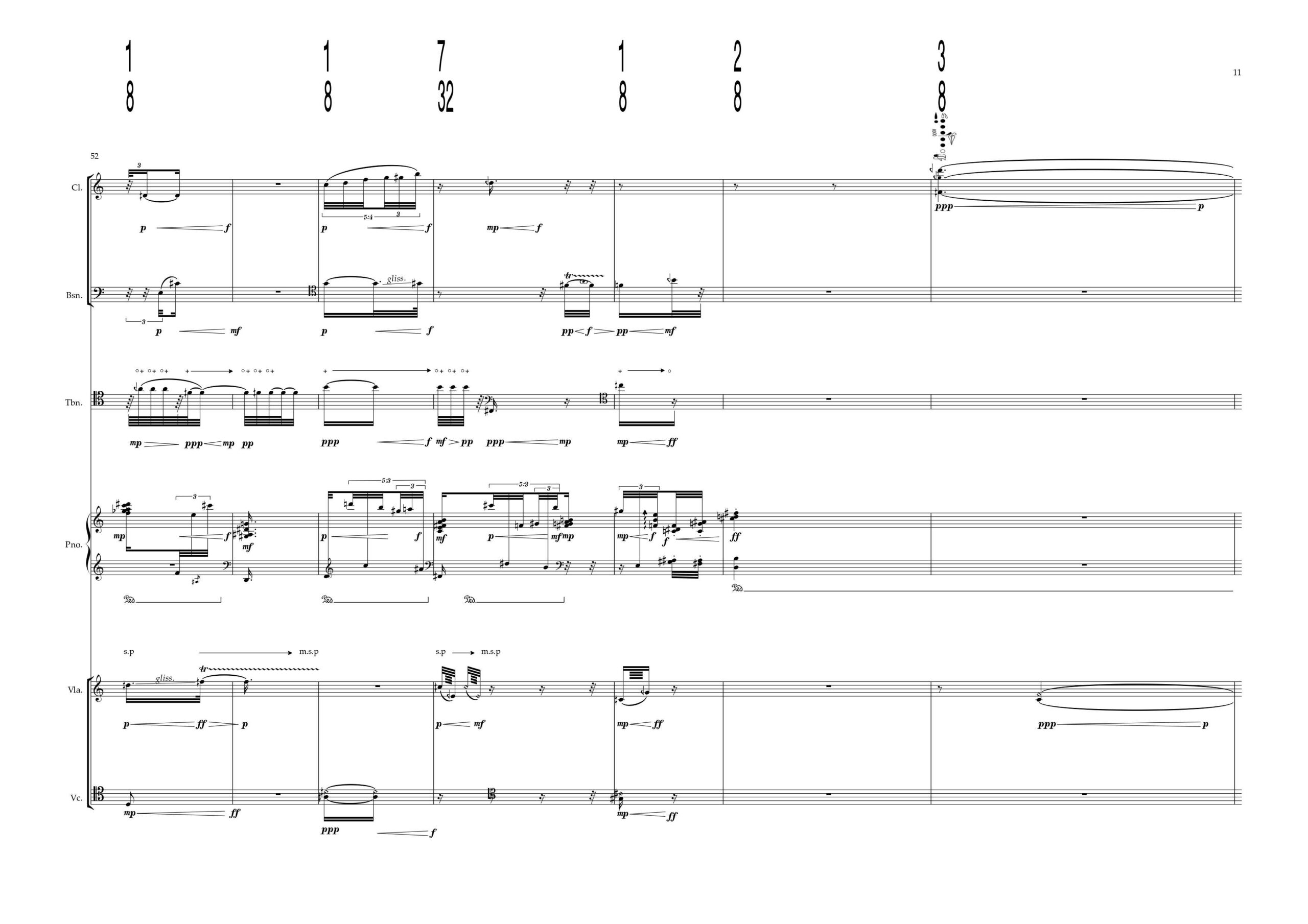

In the first movement, structure is defined by the expanding and shrinking microstructures. Each microstructure contains fragments of a Haydn quote: the last subject, from the last movement of Joseph Haydn’s last symphony (Symphony No.104 ‘London‘). The quote, a slow, cascading sequence of suspensions, captures some essence of water in its melodic fluidity.

However, the quote was more chosen for its metaphor. Haydn’s output was a vast reservoir during the common practice period: his works are the water of life for many composers. His last symphonic melody, a bittersweet coda to an era.

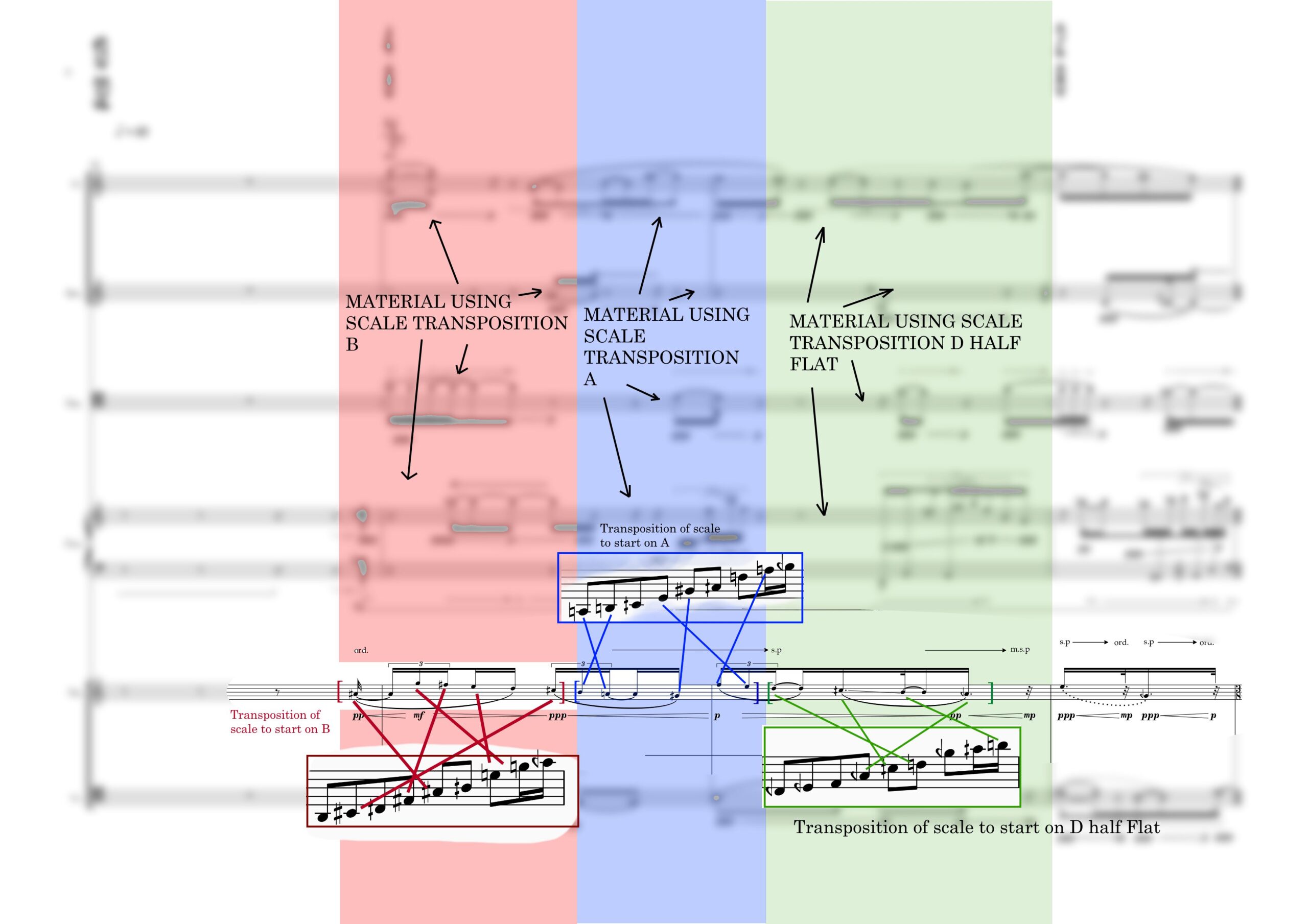

The quote is placed mostly undisturbed between the cello, bassoon, clarinet and viola. However, I re-designed the vertical harmony around it, extrapolating from material that matches my own style. To do this, I use a quarter tonal mode/scale that I’ve utilised for much of my recent work and find which transposition of my mode matches consecutively the most notes of the quote. Then I do the same for the next few notes of the sequence, usually making it so that the harmony around the quote changes more frequently towards the end of the phrase.

Parallaxenreisen (2023): Annotated score excerpt showing transpositions of the original mode.

The microstructures start stretched out and unrecognisable, and then shrink by process of natural sequences, to a size where the quote becomes more obvious. Here the quote is shown briefly close to its original harmony and tempi. After this pivot point, the structures continue to shrink and condense, once again crushing the quote to become beyond recognisable. The quote symbolises the natural water reserves in this context, eventually becoming dry and depleted into an unsatisfying final cadence.

Score excerpt of Parallaxenreisen (2023): First movement – Xanthosis (coda)

The shape of water is elusive, constantly changing and unpredictable.

In the second half of my response, or, the second movement of Parallaxenreisen, I was eager to focus a little more closely on the properties of water itself.

Tim’s work made me think of water in a new way. Specifically, I was interested in disruption.

In a vague way humans have been disrupting the Ogallala for hundreds of years: I wanted to represent this disruption locally in my music and view closely the dynamics of disruption.

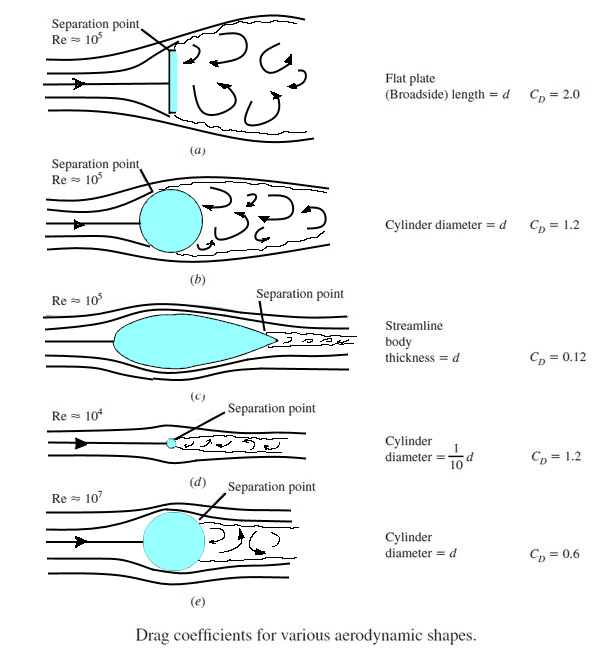

My phrases in this movement consisted broadly of three different types of displacement in water. The most complex passages in the movement are always preceded by an event or ‘disruption’, a sphere, a square and aerofoil.

The movement starts with the almost seamless aerofoil being dragged through the water, long held notes sliding and fizzling through the liquid. The second disruption is a quick introduction of a flat plate, whose separation point (marked by the intrusive vibraphone chord) is followed by a swirling muddle of instruments. The third and longest point is the effects of a sphere gliding through water, less violent and more consistent; the music on this page a vast bed of complexity.

Drag coefficients for various aerodynamic shapes. Source © Alexander Sergios Mouzouri.

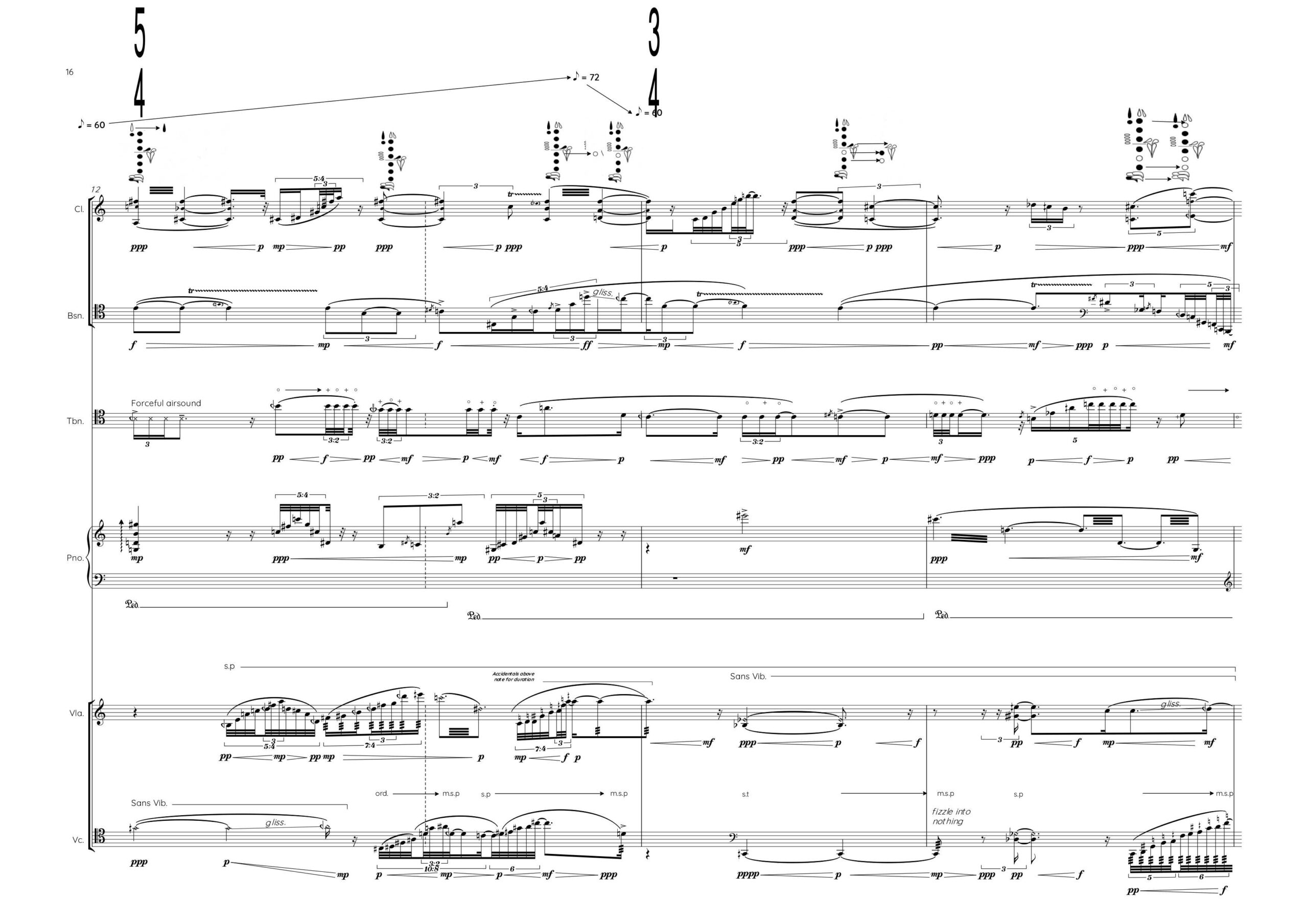

Score excerpt of Parallaxenreisen (2023): Second movement – Citrinitas

The harmony is similar in construction to the first movement. But here it is derived from the notes produced by the clarinet multiphonics: a more sustainable, natural and immortal resonance than a Haydn quote. The clarinet multiphonics, which were written first, contain the structural roots of the harmony; the surrounding vertical material is derived from the same mode as from the previous movement.

A transposition of the mode that contains the most notes shared with the sounding multiphonics is chosen to become the basis of the material being played by the rest of the instruments. This gives the harmonics a similar harmonic importance to the Haydn quote in the first movement. The intensity of the harmonic changes is most pronounced immediately after each ‘disruption’.

Score excerpt of Parallaxenreisen (2023): Second movement – Citrinitas

The music here has no edges; the result of its focus on layered phrases and strict notation, is music that moves like water and in its complexity becomes a fluid itself. The harmony is formed of natural resonances stemming from the light clarinet multiphonics floating above a bed of notation. The music in the other instruments convect and bubble eventually up to the clarinet line and infect it with their constant motion, where it too melts and becomes one with the ensemble.

The piece ends where it started, undisturbed and motionless, water that doesn’t move and hasn’t for hundreds of years.